Echoes of the Airwaves: The Legacy of the Armenian Radio Hour

It's easy to forget just how powerful radio was before the internet, but in the first half of the twentieth century the medium had an immeasurable impact on communities across the country. To illustrate that impact, we look at two records which stand as artifacts of the way early radio brought the Armenian-American community together. For Armenian communities across America the presence of “Armenian Radio Hours” wasn't just a broadcast; the sound of Armenian-language presenters and music was a comfort and a link to their homeland, serving as a pillar of identity. These shows, which broadcast around the states from Detroit to Fresno, were largely influenced by The Armenian Radio Hour that was started in Providence, Rhode Island in 1947 by Russell Gasparian.

Written by Jesse Kenas Collins

It's easy to forget just how powerful radio was before the internet, but in the first half of the twentieth century the medium had an immeasurable impact on communities across the country. To illustrate that impact, we look at two records which stand as artifacts of the way early radio brought the Armenian-American community together. For Armenian communities across America the presence of “Armenian Radio Hours” wasn't just a broadcast; the sound of Armenian-language presenters and music was a comfort and a link to their homeland, serving as a pillar of identity. These shows, which broadcast around the states from Detroit to Fresno, were largely influenced by The Armenian Radio Hour that was started in Providence, Rhode Island in 1947 by Russell Gasparian.

For decades Gasparian’s show was a hub for news and announcements, a platform for local artists, and a place to hear traditional music. Gasparian's success proved that there was a need for this kind of connection, and it wasn't long before the influence of his program spread across the country, inspiring others to launch their own "Armenian Radio Hours" in places like Detroit, Boston, and Fresno. Each show was unique to its city, but they all fundamentally served to keep Armenians in the diaspora connected to their culture and community.

In addition to his weekly broadcast Gasparian put out a series of 78rpm records in the late 1940s, which showcased some of the music and performers featured on his show. At the time these records gave listeners a chance to tune in and connect with the program on their own time. Today we are fortunate to have these discs as a document of the programming being broadcast to the Armenian community in the period. Along with this post you can hear two songs from this series, both sung by George Paloyan. The first song, Lretz Ambere, translates to "Clouds are silent" and is part of the traditional popular Armenian music repertoire. The second side of this disc is Hayr Mer, the central liturgical chant of Divine Liturgy, known as Badarak.

The representation of liturgical music alongside traditional secular repertoire illustrates the holistic perspective that Gasparian’s Radio Hour had for the community in Rhode Island. The presentation of liturgical music in particular is evidence of the way radio served as a surrogate space for congregation. This trend can be seen among the network of local radio programs across the country and is exemplified by another record from the collection with roots in radio history. Unlike the Armenian Radio Hour records which Gasparian published, the other two recordings which can be heard here were not made for commercial sale, but for internal broadcast use on the Philadelphia radio station WIP AM 76. The recordings feature the voice of Reverend Joseph Kalajian, and were made for the station at the Robison Radio Laboratory. Kaljian served as the first vicar (1946-1948) at St. Marks Armenian Catholic Church in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, before he became the pastor of the Armenian Catholic community in Detroit, Michigan. Here he can be heard singing two more foundational songs of the liturgical music, Amen Hair Sourp and Der Voghormia. Listening to a recording like this we can place ourselves in front of the radio set on a Sunday morning and hear how the sacred was made accessible in the homes of the Armenian communities.

The vision of Russell Gasparian to connect and preserve through radio and his associated recording ventures spread with these mediums across the country, helping bring the comfort of the church and songs of Armenia into the homes of Armenians everywhere. The very act of recording and broadcasting both traditional Armenian secular and liturgical music ensured that even in a new land Armenian culture would always find a way to be audible. In fact, now in its 79th year, the Armenian Radio Hour which Gasparian established is still on the air every Sunday at 9 AM on WARA 1320 on the AM dial.

Armenian Radio advertisement for new release of records run in the Feb 17th 1949 edition of the Hairenik Weekly (Image source: National Library of Armenia)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Chick Ganimian: A Driving Force of a Modern Sound

With summer in full swing, we turn our attention again to the post-World War Two generation of Armenian-American musicians who codified their unique blend of Armenian traditional melodies and American popular music. We’re revisiting a group we’ve touched on before, the Nor-Ikes Band, from a different angle. Our first piece on the group explored the career and perspective of the band's clarinetist Souren Baronian, but like many musically pioneering groups it was creative partnership that drove the work, and so we share here another set of songs which highlight the group’s oudist and driving force, Chick Ganimian. The music heard here is paired with excerpts of Ganimian in his own words, from a 1963 interview conducted with Arno Karlen and later published as “New York’s Near East” in the January 1966 edition of Holiday Magazine.

Written by Jesse Kenas Collins

Charles “Chick” Ganimian

Born: January 18, 1926, Troy, New York

Death: December 3, 1988, South Orange, New Jersey

Active years recording: 1946-1961

Label Association: Nor-Ikes Records, Atco, East West

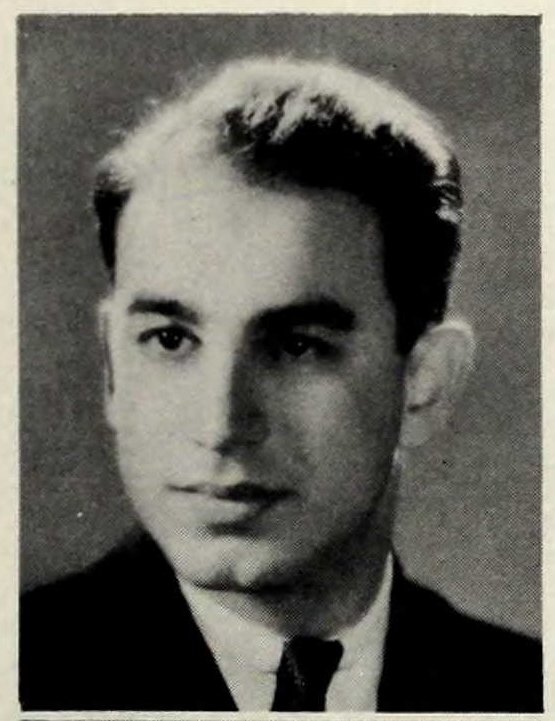

With summer in full swing, we turn our attention again to the post-World War Two generation of Armenian-American musicians who codified their unique blend of Armenian traditional melodies and American popular music. We’re revisiting a group we’ve touched on before, the Nor-Ikes Band, from a different angle. Our first piece on the group explored the career and perspective of the band's clarinetist Souren Baronian, but like many musically pioneering groups it was creative partnership that drove the work, and so we share here another set of songs which highlight the group’s oudist and driving force, Chick Ganimian. The music heard here is paired with excerpts of Ganimian in his own words, from a 1963 interview conducted with Arno Karlen and later published as “New York’s Near East” in the January 1966 edition of Holiday Magazine.

Charles Ganimian, popularly known as Chick, was born January 18th, 1926 in Troy, New York, to Nishan and Nevart Ganimian just four years after the couple's emigration from Marash, Turkey in 1922. In his interview with Arno Karlen, Chick paints a vivid picture of his musical development, first in childhood when his passion was sparked, then over the years as that passion intersected with the realities of working as a dedicated and skilled musician, spanning America’s pre- and postwar entertainment industry:

“When I was a kid," Ganimian says, "I played the violin, but I knew it wasn't really my instrument. What I liked was playing violin-and-oud duets with my father. He's from Turkey, like my mother, and he knows a tremendous number of Armenian and Turkish songs. We spoke Armenian at home, but when my parents didn't want me to understand they used Turkish. So I learned Turkish too.

When I was seventeen we moved to New York City, and the next year I went into the Army and served two years. When I got out, I didn't know what to do with myself. I was playing the oud a lot, learning from my father, but there wasn't any way for someone like me to work full time as a musician — except on Eighth Avenue, and in those days it was a much smaller scene and almost entirely Greek.

"So I made my living butchering. On the side I formed an Armenian band. I called it the Nor-Ikes. In Armenian nor means new, and ike means sunrise. We were all young American-born Armenians, and I wanted the name to show that the traditional music was having a rebirth here. Soon more bands formed, but we were one of the first. We stuck together for fourteen years, until the end of 1961.

We played Armenian weddings and parties and church affairs.

For years I went on that way — butchering, playing weekends with the Nor-Ikes. Summers I played at Armenian hotels and resorts in the Catskills. Sometimes I filled in at the Arabian Nights on Eighth Avenue. Things picked up there.

People traveled to Turkey and Greece and North Africa, heard the music, came back and wanted to hear it again. The movies picked it up. Never on Sunday was a hit. Until then, no one thought of making it on his own; if someone hired you, he hired your whole band. Now it was changing. I was getting offers of regular jobs. I went to work in the Grecian Palace, because then it had some of the best musicians. I spent a year at the Britania. I learned Greek stuff, and then the Arabic music and language. The Round-Table decided to try belly dancing, and they needed a leader for the Oriental show. I'd been building a name, and they gave me a four-week contract to try it out. The second night they extended my contract to six months. That was two and a half years ago. I've been there ever since."

Karlen’s interview was conducted in 1963 and Chick continued to work in NY at the Round-Table all the way until 1969; in addition to holding down this steady commitment he continued working numerous other venues around New York and in the Catskill Mountains. His success as a performer crossed over into pop music and jazz, and in 1967 he performed as part of Herbie Mann’s ensemble at the Newport Jazz Festival; footage of that performance can seen here. Beyond being a prolific and hardworking performer, today it is his recorded legacy that stands. In addition to the early 78rpm recordings with the Nor-Ikes, Chick led a band on the ground-breaking major label record “Come With Me to the Casbah,” recorded in 1959 and released on Atco Records. The record featured Chick’s former Nor-Ikes bandmate Steve Bogosian on clarinet, as well as the iconic Armenian-American vocalist Onnik Dinkjian. The record was pivotal in widening the exposure and popularity of the culturally-mixed music which the Nor-Ikes and other post-war Armenian-American dance bands had begun to pioneer in the preceding decades. Along with the Nor-Ikes recordings shared here, we’ve included the 45rpm single from that record, Daddy LoLo. The song features Onnik Dinkjian and is a playful American pop music rendition of the Armenian song Dari Lolo, which we hear on the Nor-Ikes record from some 20 years prior.

On December 3, 1988, Chick Ganimian passed away in New Jersey. He left behind a musical legacy and impact through his dedication and years of performance, which is felt in the continued practice of Armenian-American music to this day.

Portrait of Chick Ganimian on the cover of a promotional pamphlet of Arno Karlen’s article “New York’s Near East” (Source: Collection of Harout Arakelian)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Krikor Proff-Kalfaian: A Composer’s Journey

In the late 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century Armenian musicians began making efforts to introduce Europeans to the wonders of Armenian music. Important figures in this effort include artists we have covered in the past such as Gomidas Vartabed, Grigor Suni, and Armenag Shah-Mouradian. Among them, Krikor Proff-Kalfaian was an instrumental figure, a trendsetter who opened doors for fellow Armenian musicians. Included along with this article are two songs which make up one of the now scarcely available records self-produced by Proff-Kalfaian on his own self-titled label in 1925.

Written by Harout Arakelian

Krikor Proff-Kalfaian

Born: December 21, 1873, Bursa

Died: 1949, Fresno, California

Active years (recording): 1927

Label Association: Proff’s Records

“Yes, the power of song is great, very great! It is by grace of that power that the Church, the School, and the Theatre come and sit and place themselves in our homes, in our hearts, in the depths of our souls.” -Krikor Proff-Kalfaian, 1927

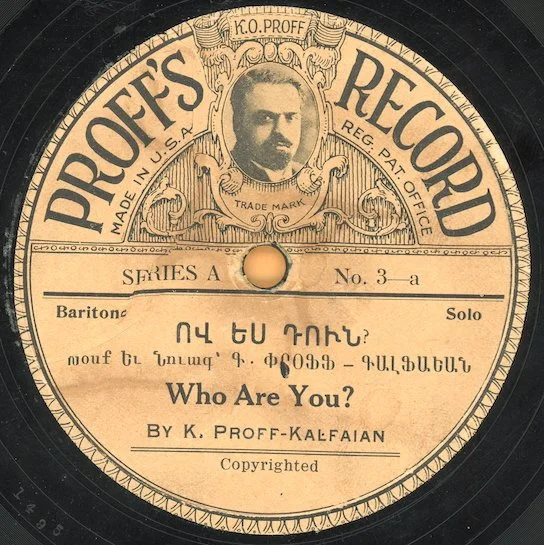

In the late 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century Armenian musicians began making efforts to introduce Europeans to the wonders of Armenian music. Important figures in this effort include artists we have covered in the past such as Gomidas Vartabed, Grigor Suni, and Armenag Shah-Mouradian. Among them, Krikor Proff-Kalfaian was an instrumental figure, a trendsetter who opened doors for fellow Armenian musicians. Included along with this article are two songs which make up one of the now scarcely available records self-produced by Proff-Kalfaian on his own self-titled label in 1925.

Krikor Proff-Kalfaian was born in Bursa on December 21, 1873. He began his music studies in Bursa, later furthering his studies in Constantinople and ultimately in France. In France, Proff-Kalfaian studied with the composer and teacher Vincent D’Indy. Through his work and relationship to D’lndy, Proff-Kalfaian became recognized for his mastery of music and was invited to be a member of the Music Composers Society of Paris in 1904.

In these early years much of Proff-Kalfian’s output is centered around the publication of sheet music, running his own publication, Groung. Published in Paris, Groung was an annual art revue which ran for just two years (from 1904-1905) and focused on the publication of his own compositions as well as one composition by the little known composer Karnig Parthamian. It was in this publication that Proff-Kalfian first printed his sheet music for his rendition of the song Groung.

The Balkan Wars convinced him to leave Europe for America, arriving in New York in 1913. Almost immediately he is advertised in the Sunday New York Times with a performance at Aeolian Hall, where he presents for the “first time in America [a] composer’s concert of Armenian Music religious and popular by K. Proff-Kalfaian.” That same year he settled in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he established a new choir for the local Armenian church. In 1918, he was invited to Fresno to become the choirmaster of the Holy Trinity Armenian Church.

When it came to the development of Proff-Kalfaian’s published compositions, two luminary singers of the period, Armenag Shah-Mouradian and Torcom Bezazian, were instrumental. Armenag Shah-Mouradian, who was Gomidas’ friend and collaborator, became a very popular performer and recording artist in both Europe and the United States. Similarly, Torcom Bezazian was a popular opera and vaudeville star whose recordings for Columbia and Victor records sold quite well. Like Proff-Kalfaian, both Torcom Bezazian and Armenag Shah-Mouradian studied with Vincent D’Indy and both vocalists extensively performed Proff-Kalfaian’s compositions: Shah-Mouradian in his repertoire on the stage and Torcom Bezazian on several of his records. Included here is Torcom Bezazian’s recording of Proff-Kalfaian’s arrangement Nor-Oror, recorded in New York on February 5, 1915 for Columbia Records. For more information and music by Torcom Bezazian see our Sound Archive feature on his work.

The recordings by Bezazian and others were popular, popular enough for Proff-Kalfaian to publish a song book before leaving Massachusetts for California. 1920 is a big year for Proff-Kalfaian: the popularity of his compositions on record and in the concert halls means he finally takes out copyrights for his compositions. In that year he had 7 songs credited to him, and dozens more thereafter. Among these copyrights is the composition titled “Who Are You/Ov Ess Toun.” Though he took out the copyright in 1920, the song wasn’t released on record until 1927. Between 1920 and 1927 Proff-Kalfaian was active leading his choir and continued to compose; in this period he even pens a patriotic song titled “O’ America,” with lyrics by the suffragist Alice Stone Blackwell. By 1927

Proff-Kalfaian also expanded his publishing efforts to recording, producing several discs performing his compositions. In December of 1925, he took out a full page article in the Asbarez newspaper alerting the readers that he’s going into production. When ready in late 1927, he published another announcement advertising his new records as “The best Christmas present;” he didn't disappoint and released his recordings just in time for Christmas.

Though his career continued into the 1930s, sadly in 1949 Proff-Kalfaian fell ill and passed away in June of that year. But the contribution he and his cohort made on the awareness and popularity of Armenian music within the Western classical music scene of the early 20th century is largely because of their tireless efforts to promote, publish, and perform their songs in print, on stage, and on record. Now 98 years later we invite you to the voice of Krikor Proff-Kalfian in song, as he asks such a simple question, “Ov Ess Toun/Who Are You.”

“And if not everyone can satisfy their musical longings with a piano, or with a violin, or with any instrument, today everyone can enjoy the benefits of Song and Music by the grace of Records. Blessed be their inventors, who undoubtedly belong to the holiest class of trailblazers of education of the human soul.

And in particular, Armenian Song records have a high and noble role to play – especially for the Armenians of America and of the entire Diaspora.” -Krikor Proff-Kalfaian, 1927

Title page to musical score, “L'esparance: chant patriotique Armenien / musique de K. Proff-Kalfaian.” Published 1918. (Image Source: From the collection of Nazik Messerlian, digitized in collaboration with the Armenian Studies Program, California State University, Fresno.)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Enoch and Peter Gamoian: Stewards of Armenian Dance Song

The history of Armenian recorded music here in America largely revolves around passionate individuals, groups, and families who take it on themselves to perform, record, and share the joy of their music and dance heritage. In 1948 in Los Angeles, the father and son duo Enoch and Peter Gamoian committed to recording a dozen dumbeg and clarinet-driven dance tunes, which have remained staples of the dance repertoire to this day. The Gamoian’s recordings, now almost 80 years old, may be relative rarities but the contribution these musicians made to ensuring the continued practice of these dances within the Fresno Armenian community is notable and lasting.

Written by Jesse Kenas Collins

Enoch Gamoian

Born: July 4, 1896 Pazmashen Kharpert | Died: Aug. 19, 1967 Fresno, CA

Active years (recording): 1948-1950s

Label Association: Rec-Art Records, M. Janigian Record Company

Peter Gamoian

Born: Sept. 1, 1925 Northbridge, MA | Died: Oct. 11, 1996 Fresno, CA

Active years (recording): 1948-1950s

Label Association: Rec-Art Records, Sarkisian Record

The history of Armenian recorded music here in America largely revolves around passionate individuals, groups, and families who take it on themselves to perform, record, and share the joy of their music and dance heritage. In 1948 in Los Angeles, the father and son duo Enoch and Peter Gamoian committed to recording a dozen dumbeg and clarinet-driven dance tunes, which have remained staples of the dance repertoire to this day. The Gamoian’s recordings, now almost 80 years old, may be relative rarities but the contribution these musicians made to ensuring the continued practice of these dances within the Fresno Armenian community is notable and lasting.

Enoch Gamoian was born on July 4th, 1895, in Pazmashen, near Kharpert. After immigrating to the United States in 1913, he settled in Whitinsville, MA, where he worked as a machinist at the Whitin Machine Works. His son, Peter, was born in Northbridge in 1925. By the 1930s, the family had moved to California, eventually settling in Fresno.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, both Enoch, a clarinetist, and Peter, a dumbeg player, enjoyed a successful musical career. Between 1948 and 1949 the pair recorded a series of seven records (14 songs) for the Los Angeles-based Armenian-owned record label Rec-Art. On several of these recordings the Gamoians are joined by Harry Parigian on mandolin. Two fundamental dance songs from these recording sessions are included here, Tamzara and Hoy Nar. These discs on Rec-Art are the only commercial recordings the father and son duo made together, though both would continue to perform and record with other musicians in the Fresno area. It seems likely that the recordings were made to some extent to showcase Peter as a dumbeg player, as they seem to be mixed to feature the dumbeg heavily. In any event the recordings seemed to serve Peter well, as in the late 1940s he performed actively both as a drummer as well as in the Karoon Tootikian Dance Troupe. Around this time he was also invited along with Harry Parigian to record four songs with Reuben Sarkisian and his orchestra, one of which, Anousiges Yeg, is included here. By the early 1950s Peter largely retired from music. In 1955 he married Jane Gamoian while working as an electrical engineer and by the 1960s he joined the Fresno police force. During this time he would occasionally join in as a musician at community events but did not record again.

Enoch, however, continued to work as a clarinetist, performing at cafes, nightclubs, and community events for the rest of his life. In particular he performed consistently in the Fresno-based band led by the vocalist Manoug Janigian, along with violinist Jack Aslanian. It is with this group that Enoch made his only other commercially available recording on Manoug Janigian’s self-titled record label. The group's recording of the tune Hassaget Cheeneare Bes is included here. It was this band that embraced the spirit of generational mentorship which Enoch had already displayed through his work with Peter, when they invited a young Richard Hagopian to play with them. This collaboration not only facilitated the musical development of one of the most respected and prolific Armenian-American musicians of the later half of the 20th century, but the ethos of intergenerational stewardship has carried through in Richard, who has passed this musical lineage down through his sons Harold, Armen, and Kay, as well as grandsons Andrew and Philip, much in the spirit of Peter and Enoch. We hope you enjoy the four Armenian dance tunes presented here, put on record by Enoch, Peter, those in their community and those they fostered, who were dedicated to ensuring the presence of music and dance in the lives of generations to come.

Label scan of M Janigian Record Company disc featuring Enoch Gamoian

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Udi Hrant: The Pathfinder

Hrant Kenkulian, known as Udi Hrant, is one of those artists whose influence and importance in Armenian culture is difficult to overstate. The irony is that this influence, though incredibly profound, has mostly been felt in the Western Armenian Diaspora and especially in the United States, while in Armenia his name is hardly known. The reason for this is undoubtedly the fact that he lived and worked for most of his life in Republican Turkey. Despite that fact, he became a model for progressive developments in oud technique. He was known for his inimitable soulful, intimate style of playing and singing, and especially his mastery of taksim, or solo modal improvisation. For Armenian oudists, in the Diaspora but also in Soviet and modern-day Armenia, he has been the primary model. He has been hailed as a legend in oud music and the greatest Armenian oud player of all time.

Written by Harry Kezelian

Hrant Kenkulian, known as Udi Hrant, is one of those artists whose influence and importance in Armenian culture is difficult to overstate. The irony is that this influence, though incredibly profound, has mostly been felt in the Western Armenian Diaspora and especially in the United States, while in Armenia his name is hardly known. The reason for this is undoubtedly the fact that he lived and worked for most of his life in Republican Turkey. Despite that fact, he became a model for progressive developments in oud technique. He was known for his inimitable soulful, intimate style of playing and singing, and especially his mastery of taksim, or solo modal improvisation. For Armenian oudists, in the Diaspora but also in Soviet and modern-day Armenia, he has been the primary model. He has been hailed as a legend in oud music and the greatest Armenian oud player of all time.

Hrant was born in Adapazar, Ottoman Turkey, in 1901 and was declared blind within two months by the best doctors in Constantinople. Despite this fact, he begged his parents to send him to the local elementary school. With a little help from friends he was able to excel, especially in math. His teachers in Adapazar, such as Mr. Krikor Mekjian (the future Fr. Agop Mekjian, longtime pastor of Our Saviour Armenian Church in Worcester, MA) and local pastor Fr. Raphael noticed his musical talent and good voice and encouraged him to sing sharagans in the local Armenian church.

When WWI broke out, Hrant’s father was drafted into the Turkish Army and never seen again. In 1915 during the Armenian Genocide, the Armenians of Adapazar were deported to the Syrian Desert by way of Konya. The governor of Konya, Mehmet Celal Bey, known as “the Turkish Oskar Schindler,” defied the deportation orders of the central government.Hrant and his mother and sisters remained in the city of Konya for the duration of the war.

Ironically, it was during the Genocide, while the family was living in complete poverty in Konya, living on leftover fruit from the neighbors and cattle entrails from the butcher shops, that Hrant first took up the oud. The blind 16-year-old developed a deep desire toward music upon befriending another young Armenian man, a deportee from Bandirma named Garabed who played the oud. Saving up pocket change, Hrant purchased a dilapidated instrument and began taking lessons from his friend, who was drafted into the Turkish army soon afterward. Although the family was often in need of kindling, Hrant protected his wooden instrument under his bed covers. He practiced it, shaking, until he was able to play the local dance melodies of Konya; soon, neighborhood women were inviting him to play at their gatherings in exchange for a plate of food or some pocket money.

After the 1918 Armistice, the Kenkulians returned to Adapazar and then relocated to Istanbul, where they rented a home in the Elmadağ neighborhood. Initially, Hrant made some pocket money playing the oud at a coffeehouse next door. Later, he accompanied his mother to the nightclub at the property of the Surp Agop Armenian Cemetery (now part of Istanbul’s Gezi Park), where she would wash dishes and he would listen to the music played by a group of local Armenian musicians.

Encouraged by his friends and improving on his instrument, Hrant began playing in local coffeehouses and nightclubs in the Beyoğlu neighborhood, known as the center of Istanbul’s nightlife. He also took lessons from violinist-vocalist Agopos Alyanakian (a fellow native of Adapazar), violinist Dikran Katsakhian, oudist-vocalist Kirkor Berberian, and master-singer Yeghiazar Garabedian (a native of Agn [Egin] in the Vilayet of Harput).

Hrant’s early career was marked by disappointment: a journey to Paris in 1921 to attend a school for the blind was prevented by the contraction of typhus; in response to this Hrant decided to stay in Istanbul and open a music store, but the music store failed in 1923; Hrant then went to Vienna for medical treatment, hosted by the Mekhitarist Armenian Catholic brotherhood, but the Vienna doctors weren’t able to do anything for his blindness. He returned to Istanbul again, playing in dive bars and coffeehouses. In 1928, he met the love of his life, Aghavni, while giving an home oud lesson to another Armenian girl from the neighborhood. Enthralled simply by her mannerisms and the sound of her voice, Hrant courted Aghavni for four months until her parents forbade her from marrying a blind musician.

Despite these setbacks, by1931 he was being called upon to play more professional gigs in restaurants and cabaret gardens. By 1934 Hrant had begun writing his own songs. Pursuant to the Turkish Surname Law of the same year, he took the legal name “Hırant Emre,” apparently choosing this name himself, which means “loving friend” or “older brother.” In the same year he met a record store owner named Ara Keğecik, who recognized his talent in the art of taksim.Keğecik agreed to finance Hrant’s first recordings. These first recordings were made in 1935 of taksims in the modes Hijaz and Huzzam. They were immediately recognized as masterpieces and quickly repressed for distribution abroad, including the United States. These two recordings were followed by two more taksims in Huseyni and Kurdili Hijazkiar (included in this post). In 1937, while on his way to a gig in the Arnavutköy neighborhood, he ran into Aghavni at the bus stop with an aunt, and invited them to come see him play; before going on stage he proposed to Aghavni over a beer and a week later she received her mother’s permission to marry Hrant.

Over the next ten years, Hrant began to find more steady work, and finally in 1947 the Turkish musicians Kanuni İsmail Şençalar, Hakkı Derman, and Şerif İçli interceded to get him hired at the more sophisticated Novotni Gazino, leading to steady work at the more upscale cabarets of 1940s and 1950s Istanbul.

It was while working at a cabaret in Instanbul in December of 1949 that Hrant was approached by a wealthy Greek-American “tourist,” who happened to be at the establishment enjoying the music. He was excited to hear that the oud player was none other than Udi Hrant, whose records he had back home at his New York City apartment. This “American gentleman,” offered to pay for Hrant to travel to the United States for medical treatment. Hrant had other plans, though. Upon arriving in New York a week before Easter in 1950, his first order of business was to attend every single Armenian church in the city for one of the Holy Week services, during which he joined in the singing as he had done in Istanbul and Adapazar since his childhood. During the holidays, he also visited with his childhood friend Hrant Nshanian and other Adapazar natives living in New York. After seeing the doctors, who of course could not cure his blindness, Hrant embarked on a concert tour promoted and financed by his Adapazar friends, performing in Boston, New York, Detroit, Los Angeles, Fresno, and Philadelphia.

The success of Hrant’s first tour inspired him to make annual or biennial trips to the United States from 1950 until 1963. He also travelled to Lebanon and France, and in 1966 to Soviet Armenia. In 1969 he bestowed the title of Udi, designating a master of the oud, upon 5 of his students/followers in the United States: Charles “Chick” Ganimian, George Mgrdichian, Harry Minassian, Richard A. Hagopian, and John Berberian. A staunch member of the Armenian Church and community until the end, he died in Istanbul in 1978.

Of the recordings included here, 3 are among his lesser known works and were pressed on the “Hrant” label in Detroit during his 1950 US tour: Serut Indzi Mishd Gayre (Your Love Burns Me Always), a Hrant original; Haley, a traditional Armenian men's dance which is introduced by Hrant's shouting: “Haley! Dance, boys, it's Udi Hrant who's playing!”; and Antif Tarer Taparesank (We Wandered For Countless Ages), a rare example of Hrant singing an Armenian patriotic song — in this case, about the rebirth of Armenia, and attributed to one Mary Tavitian.

To round out Hrant's oeuvre, we have included a taksim in the mode Kurdili Hijazkar, recorded in the 1930s, and the song Agin, a very old Armenian folk song lamenting the separation of loved ones due to emigration. This song, which originates in the Eastern Anatolian city of Agn, was most likely taught to Hrant by his teacher Yeghiazar Effendi Garabedian. Finally, we included Anush Yarin, a composition by Hrant in the mode Hijaz (his favorite) and in the 6/8 meter. This song, which along with Agin was recorded in 1950 on the Smyrnaphon label in California, was probably written by Hrant that same year, as the lyrics seem to reference his fear and loneliness traveling to America for the first time by himself (eg., “antser em dzov oo tsamak, mnatser em mis minak” [I passed over sea and land, I was left all alone]) and being apart from his beloved Aghanvi (“Anush yares heratsa” [I went away from my sweet love]). Hrant's strong faith, which he mentions often in his memoirs, is also in evidence here: “Asdoodzo gamke ullah, tzerke tne mer vrah” (May the will of God be done, may he place his hand upon us).

Advertisement for a concert presented by the Sepastia Compatriotic Union of Philadelphia, featuring Udi Hrant, visiting singer Shakeh Vartenissian, and Philadelphia's Arziv Band. Published in the Philadelphia Groong Weekly newspaper on Nov 17, 1950. (Image source: National Library of Armenia)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Special thanks to Paul Sookiasian for finding and sharing the Philadelphia concert ad from Groong Weekly

Gomidas: Music and Memory

On April 2, 2025, Governor Maura Healey declared April as Armenian American Heritage Month in Massachusetts. To honor this, the Sound Archive is spotlighting Gomidas Vartabed through a special song selection and a rare archival discovery that raises the question: what might have changed in his life and Armenian music if a missed opportunity had been realized?

Armenians began settling in the U.S. in small numbers by the mid-19th century, with Worcester, Massachusetts, becoming the first organized community. In 1891, Worcester's Armenians founded the first Armenian Apostolic church in America. Some, like Moses Gulesian—a key figure in preserving the USS Constitution—later moved to Boston. Gulesian also worked on the 1901 renovation of Boston’s Old State House, where a time capsule was placed in a copper lion. When opened in the 2010s, it revealed a U.S. diplomatic report from 1897 documenting the Ottoman Empire’s massacres of Armenians, a striking historical connection uncovered by architect Don Tellalian.

Written by Harout Arakelian

Gomidas Vartabed / Soghomon Soghomonian

Born: October 8, 1869, Kütahya, Ottoman Empire

Death: October 22, 1935, Paris, France

On April 2, 2025, the Governor of Massachusetts, Maura Healey, proclaimed April as Armenian American Heritage Month. The Sound Archive wishes to contribute to this heritage month by remembering Gomidas Vartabed through a unique selection of songs and a little-known archival find regarding the history of the fledgling Armenian community of early 20th century Boston. It’s a find that leaves a lingering question of “what if…?” What might have changed in the life of Gomidas Vartabed and the course of Armenian music history if this unfulfilled opportunity was in fact realized?

By the mid-19th century, there were scatterings of Armenian individuals throughout the United States, such as the few Armenians who joined the Union Army during the American Civil War (most as field doctors). The established communities didn’t start developing until the last quarter of the 19th century. The industrial city of Worcester is known as the first Armenian community in Massachusetts. When in 1891 the Worcester community established the first Armenian Apostolic church in the US, The Church of Our Savior, it is rumored that Khrimian Hayrig recorded a congratulatory message on an Edison wax cylinder.

Some of the Armenian residents of Worcester would later resettle in Boston, including figures such as Moses Gulesian, who led the efforts to save the USS Constitution, the US Naval vessel named by George Washington that later earned the nickname of “Old Ironsides.” Gulesian, a native of Marash, was also involved in 1901 renovations conducted at Boston's Old State House. During this construction, a time-capsule was placed in the head of the copper lion atop the Old State House. When the shoebox-sized capsule was discovered in the early 2010s, the first item uncovered was a leather bound book titled “Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, with the Annual Message of the President Transmitted to Congress December 7, 1896, and the Annual Report of the Secretary of State (Washington, 1897).” When Boston architect Don Tellalian further investigated, it was discovered that the content of the book was official US diplomatic correspondence describing the Ottoman oppressions of Armenians during the Hamidian massacres of 1895-6.

While there are many stories and histories documenting the Armenian experience in Boston, this article will highlight a short report published on May 18, 1907 in the Hairenik Daily newspaper. The headline reads, “The Parish Council of Boston and Its Decisions.”

The brief but informative article laid out a four-point agenda for the community. The parish priest Sarkis Tashjian presided over the meeting. Of the four decisions announced that day, one bullet point stands out more than the rest. It reads: “It was decided to find a way to bring Gomidas Vartabed here from Europe in order to introduce Armenian music, whether to Armenians or to foreigners, just as he has successfully done in Paris recently.”

While the attempt to bring Gomidas Vartabed to the US did not occur, within two years of that parish meeting (in 1909), the priest’s oldest son, Mardiros Der Sarkis Tashjian recorded a set of six songs on the Columbia Records label. He became the first to record Armenian language music in America. The same year in Gyumri(then Alexandropol), Gomidas Vartabed was recorded by the Gramophone record company. The Gyumri recording sessions are the only known recordings of Gomidas’ voice. Later in 1914, for recording sessions with the Blumenthal-run Orfeon records, Gomidas accompanied vocalist Armenag Shah-Mouradian on the piano.

The Armenian Museum of America’s musical selections return us to these 1914 recording sessions in Constantinople featuring Gantche Groung and Yes Lessetzi. The next two songs we present were a part of a recording session that remains somewhat unclear. The session was organized in 1927 under the name Gomidas Choir of Constantinople directed by Mr. Z. Sarian. This set of 10 songs were recorded by the British His Master’s Voice label. According to an announcement published in the 1928 almanac of Istanbul’s Surp Prgich Armenian Hospital, the proceeds from the record sales would help with the costs of Gomidas’ rehabilitation in France. Only one of the five discs was reissued by Armen-Vahe’s The Orient label in the 1930s, featuring the compositions by Gomidas Vartabed, Sareri Vrov Gnats and Andzrev Egav.

From top left to lower right: Gomidas, 1901, Paris (Image Source: Komitas Museum). May 18, 1907, Hairenik Daily Newspaper (Image Source: National Library of Armenia). Reverend Sarkis Tashjian (Image Source: Project Save Photograph Archive). Gulesian Factory, 1901, Boston, Lion heads for the Old State House (Image Source: Project Save Photograph Archive.)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Anoush Karoun: A History of a Beloved Song

The art song Անուշ Գարուն (EA: Anush Garun; WA: Anoush Karoun) was composed by Daniel Ghazarian (1883–1958) in Soviet Armenia, likely in the late 1920s. Ghazarian, initially a shoemaker, was encouraged by his teacher and fellow composer Grikor Suni to pursue music. He moved to Baku in 1907, then Tbilisi, where he graduated from the Tbilisi Music College in 1911. After surviving WWI and the Russian Revolution, he graduated from the Tbilisi Conservatory in 1921. Ghazarian became a key figure in modern classical music education in Armenia and the Caucasus.

Written by Harry Kezelian

Today we are pleased to present a special installment of the Sound Archive, focusing on one of the best-loved Armenian songs of the 20th century: Anoush Karoun.

Here at the Sound Archive we tend to build our articles around specific artists and their careers, but we deemed it valuable (and in keeping with the season!) to focus this month on a particular composition, which has been interpreted by so many Armenian artists across the world and across genres and styles.

The art song Անուշ Գարուն (EA: Anush Garun; WA: Anoush Karoun) was written in Soviet Armenia, apparently in the late 1920s, by the prolific composer Daniel Ghazarian (b. 1883, Shushi, d. 1958, Yerevan). At age 24, Ghazarian was encouraged by his singing teacher, as well as by fellow Shushi native composer Grikor Suni, to leave his trade as a shoemaker and attend music school. Ghazarian left for Baku in 1907 and the following year transferred to Tbilisi. He graduated from the vocal division of the Tbilisi Music College in 1911 and after surviving the upheaval of WWI and the Russian Revolution (apparently by travelling from city to city organizing choral groups for local students), he graduated from the newly established Tbilisi Conservatory in 1921. A composer, arranger, conductor, and especially a teacher for decades, he was one of the major founders of modern (Western) classical music education and practice in Armenia and throughout the Caucasus.

The song seems to have taken off almost as soon as it was first published. In 1929, Ghazarian made his first musical appearances outside of the Caucasus, giving acclaimed concerts in Moscow and Leningrad (St. Petersburg), as conductor and director of the performance of his own pieces. According to critics at the time, several pieces showcasing Ghazarian’s personal style were especially well received. Among these was Anoush Karoun.

The song continued its journey around the world when it became part of the consciousness of the Armenian Diaspora. Its popularity was especially universal in the Armenian community of the United States.

The classic melody seems to have been first unveiled to the Armenian-American community in 1935, when a performance of Anoush Karoun by one Loretta N. Movsesian (soprano, with piano accompaniment) was released on Armen Vahe’s The Orient label.

We have discussed Armen Vahe’s career in the record business before. Most of the releases on The Orient label were reissues of recordings made by RCA and others, especially from Turkey. This one was no different; Anush Garoon was recorded on the Polyphon label in 1929, in Persia (Iran), credited to Loretta N. Movssessian.

As noted, Armen Vahe was also part of the editorial board of the Hayrenik newspaper, which advertised the new reissue disc in August, 1935. In subsequent ads, the fact that this song was “beloved” and “sought-after” was frequently underscored by Armen Vahe. It also seems like he may have pressed more copies than even he could sell, since they were later used as giveaways, and it is not unusual to find several copies of this particular disc in old collections.

Throughout this research team’s collective work with the Museum and elsewhere, we have come across numerous home disc recordings of Armenian immigrants and Genocide survivors made in the 1940s and 50s in the US. In nearly every collection, we seem to inevitably come across a rendition of Anoush Karoun, often performed by a solo female voice. And that’s in addition to the plentiful copies of commercial disc recordings. The popularity of the song is obvious to anyone who has taken a look at the musical culture of Armenian-Americans.

But in addition to the Movsesian recording's release in the US, the song gained acceptance and popularity throughout the Diaspora: the Museum’s collection includes renditions by Martin Keoshaian (USA), Hovsep Seraidarian (Lebanon), and Angele Varjabedian (France) — all of which we have included in this post — among others.

By the 1960s, the song Anoush Karoun had solidified itself in the Armenian-American consciousness. In the January 1966 issue of Holiday magazine, writer Arno Karlen, in a piece on NYC's Near Eastern music scene, described a performance of the song by iconic oudist/vocalist Chick Ganimian to a group of diehard fans at the Cafe Feenjon in Greenwich Village at 5:30 in the morning, opining that “Anoush Karoun…. is to the Armenians what Eli Eli is to the Jews — a sort of unofficial anthem of their sorrows. It tells of the happy days in springtime in the wild mountains of Armenia, before the great slaughter by the Turks, the annexation by Russia.” Along with the centuries-old diasporan anthem Groong (the Crane), it was one of two songs that George Mgrdichian chose to perform as oud solo pieces on the early kef album Oriental Delight (1958) by the Philadelphia Gomidas Band (billed as the “Hank Mardigian Sextet”). These two solos were the first step in taking homegrown Armenian-American folk music to a higher artistic level, with the oud eventually reaching Carnegie Hall in Mgrdichian's hands. The Anoush Karoun solo has been credited with influencing a generation of oudists in a new direction by no less than Ara Dinkjian.

It is fitting then, that we end this post with the classic 1963 New York recording of Anoush Karoun by Kay Armen (vocalist) and George Mgrdichian (oud accompaniment). At the apex of post-war, mid-century American society, a month before the Kennedy assassination, the venerable Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) hit upon a novel method of fundraising: sending a free vinyl record to their vast mailing list of 25,000 people. The small 7” record they produced played at 33 rpm, like an LP, but was really a single: on one side it included a message about giving to the AGBU (by Board President Alex Manoogian, speaking in Armenian, and Kay Armen herself speaking in English), and on the flip, the song Anoush Karoun by Miss Armen, accompanied by piano and Mgrdichian’s oud.

The lyrics of Anoush Karoun speak not only to the longings of Armenians during the Soviet Era or the survivors of the 1915 Genocide (like those among whom this song was so popular during the 20th century), but also to today: composer Daniel Ghazarian was born in Shushi, Nagorno-Karabagh, now occupied by Azerbaijan, and his ode of longing for the return of the sweet spring is pertinent now more than ever.

Lyrics:

I’m waiting for you, sweet spring

And for the coming, with you, of my flower-sweetheart

You are longing for the burning sun

And I, for the springtime sweetheart of my life

You have a rose which enchants you

And fades along with your life

I have a sweetheart, eternal spring

Who remains burning in my soul

I’ll wait with sleepless eyes

I’ll keep the love burning in my heart

I’ll pluck a bouquet from the rose bush

And bring it as a gift to my beloved sweetheart

Portrait of the composer Daniel Ghazarian to whom the song Anoush Karoun is attributed, with a group of students in Kaghzvan circa 1914 (image source).

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

The Songs of Pepo

Our primary focus has been on commercially-released recordings, lacquer/home recordings, and re-issued records. While we’ve discussed Armenian films previously, with this article we shift our attention to an experimental recording: not quite a soundtrack but a medley of film music from the 1935 movie Pepo, the first Armenian language sound film produced in Soviet Armenia.

Written by Harout Arakelian

Soundtrack of the movie Pepo (1935)

Label Association: Rec-Art Recordings

Our primary focus has been on commercially-released recordings, lacquer/home recordings, and re-issued records. While we’ve discussed Armenian films previously, with this article we shift our attention to an experimental recording: not quite a soundtrack but a medley of film music from the 1935 movie Pepo, the first Armenian language sound film produced in Soviet Armenia.

The discs presented today are bootleg recordings from the music for Pepo. While it remains unknown how the film music and audio track were extracted from the original film or how the source material was acquired from the film reels, this remarkably experimental act provided a unique way to preserve the music from a very important work of cinema.

Setrak Sourabian, the producer of these discs, was an important and seminal figure in the Armenian theater community in America. Born in Tiflis on March 6, 1894, he first appeared on stage in 1915; by the 1940s, Setrak Sourabian had been recorded as a singer (Sokhag/Sohag record label), acted, directed, wrote, and performed in countless stage productions. Coinciding with the pressings of these records and in celebration of playwright Gabriel Sundukian’s career, Sourabian staged a production of Pepo on May 7, 1950 at the Wilshire Ebell Theatre in Los Angeles.

The playwright Gabriel Sundukian (b. July 11, 1825, Tiflis) is considered the founder of modern Armenian drama. In 1870, he published Pepo as a three-act comedy. The story takes place in Tiflis (modern day Tbilisi) and tells the story of a clash between the two main characters, Pepo, the honest fisherman, and the greedy moneylender Zimzimov. The first performance took place in 1871 in Tiflis and became a great success.

In 1935, work began on an adaptation of Pepo, by the film director Hamo Bek-Nazarian. Bek-Nazarian (b. May 19, 1891, Yerevan) was a leading director of Soviet Armenia, having already made the first film produced in Armenia, Namus (1925). For the adaptation of Pepo, Bek-Nazarian worked with the young musician Aram Khachaturian (b. June 6, 1903, Tiflis), the writer and poet Yeghishe Charents (b. Mar. 13, 1897, Kars), and Hrachya Nersisyan (b. Nov. 24, 1895, Izmit), the actor who played the lead role of Pepo.

By late 1935, the movie premiered in the United States. The headline in the October 10 New York Evening Post read, “Armenian Film “Pepo” Has Cameo Theatre Premiere.” And soon the film began travelling North America with screenings in Providence (Nov. 22, Modern Theatre), Worcester (Nov. 30, Regent Theatre), and elsewhere. By 1937 the film traveled to the West Coast with screenings in both Fresno (March 2, Fulton Theatre) and Los Angeles (March 22, Roosevelt Theatre). In 1952, at the Fulton Theatre in Fresno, the film was screened as a double feature along with Arshin Mal Alan. The film continues to be screened in art houses and film festivals throughout the world.

For these unorthodox recordings, Sourabian partnered with Nazareth Arzoumanian (b. May 3, 1890, Yozgat), the owner of Rec-Art Recordings. Established in the mid-1930s, the studio specialized in radio transcriptions and personal recordings, becoming a key spot for Armenian artists in Los Angeles. Arzoumanian also produced "The Armenian Hour" and "Oriental Moods" radio programs. The pressing process resulted in a disjointed listening experience, with abrupt scene cuts, fragments of dialogue, and incomplete songs as they appeared in the film.

The content on these records consists of a medley of songs taken from various scenes in the movie. The Song of Pepo (also known as Fisherman’s Song) & Gagooli’s Feast are taken from the opening scene of the film, while Keor Oghli is the closing sequence of the film. The other recordings include a vocal solo by Hasmik (Tagouhi Hakopyan), who played the role of Shushan. The fourth disc includes a portion of Sayat Nova’s Dun En Gelkhen and an up-tempo version of the dance Gindavouri.

The great filmmaker Rouben Mamoulian (b. October 8, 1897, Tiflis) had the following to say after a screening of the movie: “My ideas on the role of sound film were strengthened when one day, sitting at a corner of the movie theater, I watched the Armenian talking movie, Pepo… Glory to the miracle of film, because here, in the heart of Hollywood, I was able to see the face of my country and hear its voice... It was incredible to see on the screen the scenes of my hometown Tiflis, to watch live and colorful characters skillfully composed by Sundukian, and to hear the soft music of the Armenian language.” (Mshag Newspaper, 1936).

Still from the film Pepo

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Richard G. Hagopian: An Educator Through Music

When most people hear the name Richard Hagopian, they might think of the master oud player and singer who has made an immeasurable impact on the modern history of Armenian music in America. While his work and impact deserves the fullest exploration, here we take a look at a lesser known musician by the same name.

Richard G. Hagopian carved a unique path with his musical and educational career, stradling the worlds of the concert hall, Armenian music, and music education. Within this career he left us with only one commercially produced 78rpm record from 1949, but within the Museum’s collection, two unreleased lacquer records from 1951 have recently surfaced, bringing his known recorded output to a total of six songs.

Written by Jesse Kenas Collins

Richard G. Hagopian

Born: July 16, 1920, New York, NY

Death: March 31, 1971

Years Active Recording: 1949

Label Associations: Richard Hagopian Records

When most people hear the name Richard Hagopian, they might think of the master oud player and singer who has made an immeasurable impact on the modern history of Armenian music in America. While his work and impact deserves the fullest exploration, here we take a look at a lesser known musician by the same name.

Richard G. Hagopian carved a unique path with his musical and educational career, stradling the worlds of the concert hall, Armenian music, and music education. Within this career he left us with only one commercially produced 78rpm record from 1949, but within the Museum’s collection, two unreleased lacquer records from 1951 have recently surfaced, bringing his known recorded output to a total of six songs.

Richard was born Dickran Garabed Hagopian on July 16, 1920 in New York City to Garabed Hagopian and Taolinda Mouradian. By 1938 the family was living in Cambridge, MA where Richard attended the Rindge Technical High School. There he studied violin, going on to study at the New England Conservatory of Music, where he sat as a first violinist in The Conservatory Orchestra of 1939. In 1942 he was employed by the National Youth Administration Symphony Orchestra, a short-lived endeavor of the National Youth Administration, which brought professional opportunities to young musicians. The program ended in order to devote more resources to WWII. Richard joined the war effort as well, serving as a Private in the Army from 1942-1943.

After his service, Richard took a position with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in 1945. Just a few years later, he made his way back home to the Boston area and established his own orchestra, which provided music for Armenian cultural events throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s. In 1949, as part of the group's promotional efforts, Richard established the label Richard Hagopian Records out of his Beacon St address in Somerville, MA.

The first two songs presented here come from that 1949 record and represent the sole commercially released output of the label. On one side, the record is a medley of the Armenian dances Sareree Achtcheeg, Ouzoondara, and Shalakho. The other side is an arrangement of the traditional choral song Alakiaz, along with orchestral arrangement. Recently, two unreleased lacquer discs recorded in 1951 were found in the Museum’s collection and are shared here for the first time. The first disc includes an elegant instrumental arrangement of the famous song Anoush Karoun (Sweet Spring) led by a rich string section. We’ll be taking a deep dive into the story of this iconic song later this spring. The other side of this disc is Mashdi Pat or Mashadi Ibad, which is based on an operetta by Uzeyir Hajibeyov about a young couple whose relationship is threatened by an ill-fitted arranged marriage plan. The song was first recorded in New York City in 1927 by Setrak Sourabian and George Shah-Baronian and released on the Sohag label. In 1949 The Vosbikian Band also released a version of the tune. The second lacquer disc includes Sareree Verov Kenar, a work attributed to Komitas Vartabet and arranged by Hagopian for piano and violin. The second song on the record is titled Oh Beauty and is an upbeat medley based on the popular song Sheg Mazerov. The song was originally written by Hovsep Shamlian but in 1951 a version was written by William Saroyan and Ross Bagdasarian under the name Oh Beauty, and released along with the tune Come On-A My House. More traditional arrangements were recorded and circulated in the 1940s by groups including The Vosbikian Band and The Nor-Ikes. Hagopian takes elements from these various renditions of the time and blends them with a song recorded by The Gomidas Band under the name Hye Dugack (Armenian Boys), all while imparting his unique orchestra perspective to the tune.

In addition to his performance and recording work Richard took up a career in music education. In 1965 he was serving as the Music Director for Watertown Public Schools and working along with other music educators in the area to publish papers and host workshops to expand the pedagogy for teaching young musicians both compositional and performance techniques. Sadly, Hagopian passed away at the early age of 50, on March 31, 1971, of a heart condition. Richard began his music education working with talented musicians and directors at institutions like the New England Conservatory; by the end of his career, Richard was able to give back to his community through his work as a music director and educator. While we are left with only a few audio recordings of Richard and his Orchestra, we are glad to expand that number of available recordings from two to six with the discovery of the unique records presented here.

Portrait of Richard G Hagopian from the 1941 Yearbook of New England Conservatory of Music (Image: Internet Archive)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Sound Archive 2024: Year in Review

As we close out the fourth year of the Sound Archive project here at the Armenian Museum of America, we are thrilled to have compiled 40 presentations in that time. Each has been dedicated to a different story of Armenian artists who made an impact on the musical and cultural heritage through the legacy of their audio recordings. Across those 40 articles, we have shared 156 different recordings, all digitized and restored from the Museum's expansive collection of early to mid-20th century 78rpm records. Presented here are some highlights from this year's selections.

Written by Jesse Kenas Collins

As we close out the fourth year of the Sound Archive project here at the Armenian Museum of America, we are thrilled to have compiled 40 presentations in that time. Each has been dedicated to a different story of Armenian artists who made an impact on the musical and cultural heritage through the legacy of their audio recordings. Across those 40 articles, we have shared 156 different recordings, all digitized and restored from the Museum's expansive collection of early to mid-20th century 78rpm records. Presented here are some highlights from this year's selections.

One of the strongest areas of the Museum’s 78rpm collection is the output of the first generation of Armenians who came to America in the early 20th century, largely coming from Kharpert and Dikranagerd. This generation made a remarkable effort in the 1920s to document their folk and popular music through numerous independently run record labels. This year we looked at musicians from that cohort on the East Coast, including Kaspar Janjanian and Megerditch Douzjian. We also covered the work of that generation in continuing independent record production in the 1940s and 50s on the West Coast, focusing on the couple Reuben & Vart Sarkisian. Also from this mid-century period, we celebrated the music of iconic Massachusetts born band leader and clarinetist Artie Barsamian. The article on Barsamian continued the Sound Archive’s efforts to collaborate with experts and researchers in the field of Armenian music. In this case, the body of the article was excerpted with generous permission from Hachig Kazarian’s excellent book Western Armenian Music: From Asia Minor to the United States (available in the Museum's bookstore.).

Two other features this year explored the aesthetic shifts and integrations of popular film and orchestra music that developed in the 1940s and 1950s, mainly on the West Coast. The artists Zaruhi Elmassian and Setrag Vartian and Hrach Yacoubian describe different facets of those aesthetic shifts. Similarly, the works of Kurken M. Alemshah and Shara Talyan give us a window into the hybridization of Eastern Armenian folk music with Western classical orchestra and operatic traditions. The work of these artists shows how this process was impacted by the fluid movement of artists studying and working across Europe, the Soviet Union, and the United States in the late 1930s until the late 1940s.

This year, we were also able to identify the voice of the renowned oudist and teacher Krikor Berberian. We identified Berberian as the performer on a record by the label Orfeon Records, which was a reissue of a recording Berberian made in 1910-1912 in Constantinople. This record became the key to identifying numerous other recordings of Berberian which were reissued (without attribution) on the labels Odeon and Popular Haygagan.

The final two subjects we covered this year were each special in their own right. The first exemplified the significance of audio recording in presenting non-musical works, and is a beautiful recitation of poetry by the famed Armenian actor Ardashes Kmpetian that was recorded and produced by the independent French label Ararat in 1953. Last, but certainly not least, we were thrilled to share the solo voice recording of Dr. Elizabeth Gregory, singing the Van regional folk song Le Le Jinar on a one-of-a-kind home recording made as part of a private project exchanging folk repertoire with Yenovk Der Hagopian.

After four years, having shared dozens of stories and over 100 pieces of Armenian recorded sound history, we are still just scratching the surface of the Museum's audio holdings. We look forward to sharing more of this history with you in 2025 and we hope the recordings shared here bring you joy as we head into the new year.

Cover for the 1928 catalog of the independent Armenian music record label Pharos Records. (Scan: Armenian Museum of America.)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Megerditch Douzjian: An Everlasting Star

Megerditch Douzjian, born in Dikranagerd in 1896, arrived in the U.S. in 1921 after surviving the Genocide and World War I in hiding. He settled in New Jersey, where he became involved in the Hunchakian party and the Paramaz Dramatic Association. His success on stage led to a recording career, beginning in 1925, where he recorded numerous songs for various labels and he continued performing with the Paramaz troupe until his last performance in 1947.

Written by Harout Arakelian

Megerditch Douzjian

Born: May 10, 1896, Dikranagerd, Ottoman Empire

Death: April 18, 1958, Union City, NJ

Years Active Recording: 1925-1933

Label Associations: Margosian Records, M. G. Parsekian Records, Pharos Records, Yeldez Records

On April 29, 1921, Megerditch Douzjian, aged twenty-five, arrived in the United States after a sixteen-day voyage from Marseille on a ship named Braga. He was born in Dikranagerd on May 10, 1896, where his father was recognized as a half doctor, half apothecary. During the Genocide and the First World War, Douzjian remained in Turkey, living in hiding and extreme poverty.

During the Armistice period he found his way to Cilicia. In 1921, Douzjian, like many fellow Dikranagerdtsi musicians, settled in West Hoboken (now Union City) New Jersey. He became a member of the Hunchakian party and joined the Paramaz Dramatic Association, which he performed with over the decades. In 1922, he married Azniv (Elsie) Fanarjian while living at 721 Highpoint Avenue in West Hoboken. Azniv arrived in America in 1908 with her parents Hovhaness and Lucia (all born in Dikranagerd). The couple had two children, Vartouhi, born 1924, and John, born 1927. Douzjian found work in the silk mills, which he segued into a successful career in the dry cleaning industry.

His success on stage with the Paramaz Dramatic Association led to his recording career. His discography consists of a range of songs from Western Armenia. Beginning in 1925, he recorded three songs for Vartan Margosian’s label (Margosian Records). In 1927, he recorded a total of 10 songs: two songs for the M. G. Parsekian label and an additional eight for the Pharos record label (by this time, Pharos had bought the catalogs of M. G. Parsekian and the two songs by Douzjian were reissued on the Pharos label). It was during these sessions that Douzjian recorded his most popular song, Iprev Ardziv (Zoravor Antranigi Anmah Hishadagin), an ode dedicated to Armenian revolutionary General Antranig Ozanian, written by Ashough Sheram (Grigor Talian). On the flip side of the disc is the ode to the freedom fighter Bedros Seremjian, Vekerov Li, written by Ashough Farhad (Khatchadour Gevorkian).

In 1928, Douzjian started his own record label, Yeldez Records, releasing three discs. This set of recordings would later be reissued by the Pharos label. The first song featured on his new label is the first known recording of the song Dari Lo Lo, titled on the record as Shad Anoush. While the origins of the lyrics are unknown, the song became a standard of the Armenian-American repertoire. Douzjian had two other recording sessions with the Pharos label, recording six songs in 1929. Among these songs is his unique incorporation of the Lezginka dance melody for the song Akh Im Aghvor Meg Hadig, a love song written as a duet but here performed by Douzjian as a soloist. Ending an era of Armenian independent labels, he recorded his final two songs on the Pharos label in 1933.

Following his recording career, Megerditch Douzjian continued to perform with the Paramaz acting troupe and his last known performance was in the three-act comedy, The Village Bride and The Big City Groom, staged in Union City on March 16, 1947. Upon his death in 1958, a fellow actor wrote of Megerditch Douzjian: “His voice and songs would brighten the room. The memory of his voice on his recordings will be appreciated long after his death.”

Portrait of Mgerditch Douzjian from the 1928 Pharos Records Songbook

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Kurken M. Alemshah: From Bardizag to Paris

This installment of the Sound Archive highlights recordings made in late 1947 by Armenian composer and conductor Kurken Alemshah in Paris, shortly before his untimely death. A significant figure in modern Armenian music, Alemshah merged traditional Eastern Armenian melodies with Western classical techniques, drawing inspiration from composers like Sayat Nova and Gomidas Vartabed. The recordings feature the soprano Asdghig Arakelian and showcase Alemshah's talents, which had flourished throughout his career as a teacher and composer between Paris and Venice. Despite passing away just before a performance in Detroit, Alemshah left a lasting legacy, influencing Armenian classical music, with his works being featured posthumously by the Armenian National Chorus shortly after his death.

Written by Jesse Kenas Collins

Kurken M. Alemshah

Born: May 22,1907, Bardizag, Ottoman Empire

Dies: December 14, 1947, Detroit, Michigan

Active years recording: 1947

Label Association: Colibri

In this installment of the Sound Archive we turn our attention to a set of recordings made in Paris, France by the acclaimed Armenian composer and conductor Kurken Alemshah. As a contemporary of modern Armenian composers such as Parsegh Ganatchian and Mihran Toumajan, the work of Alemshah follows in the Eastern Armenian musical tradition, characterized by interpretations of Armenian folk melodies rendered through the compositional techniques of Western classical music. The recordings presented here were made in late 1947, just prior to Alemshah’s sudden passing. They show his work at the height of its development and feature the powerful voice of the soprano Asdghig Arakelian.

Kurken Alemshah was born on May 22,1907 in Bardizag, a district of Izmit built at the foot of the St. Minas Mountain. At the age eight his parents sent him to Venice, Italy to escape the Genocide. There the young Alemshah was able to study at the Murad-Rafaelian Armenian College. Already showing musical promise at the age of sixteen, he went on to study music at the Milan Conservatory. There he developed his skills as a composer of classical European music, while merging this training with his study of and appreciation for traditional Armenian folk music. Like other artists working in this idiom Alemshah’s work was grounded in and often included arrangements of works by Sayat Nova and Gomidas Vartabed as well as such as Ashoug Sheram. In fact the first song presented here, Na Mi Naz Ouni, is an arrangement of a song attributed to Ashough Sheram, while the tunes Erangui and Mi Khosk Ounim are attributed to Gomidas and Sayat Nova respectively. The last composition, Nazère, is an original composition by Alemshah.

By the time these recordings were made in 1947 Alemshah had a decades-long career working as a teacher, composer, and choral director, primarily between Paris and Venice. The recordings here were published on two four-disc sets of 78rpm records on the Colibri record label and were manufactured in Paris, France. The albums received wide distribution in the United States with advertisements in the Armenian papers at the time of its release, promoting their availability at eight record stores on the East Coast from Philadelphia up to Detroit. Both albums present a selection of orchestral works as well as piano and soprano duets, featuring the accomplished singer Asdghig Arakelian with Kurken Alemshah on piano. Arakelian was a soprano working in Paris, whose career began upon graduation from college in 1920; she was working and touring as late as 1962.

Sadly Alemshah’s career was cut short just around the time of the album's release. In the fall of 1947 Alemshah came to the United States for an extended tour of the East Coast. During that trip he presented works at venues as prestigious as New York Town Hall, presenting his Armenian orchestral and choral works. But on December 14th Alemshah suffered a heart attack and passed away, one day prior to his scheduled appearance in Detroit. Despite his untimely passing Alemshah made a profound impact on the character of modern Armenian classical music. Just two years after his passing his music would again fill the air of New York's Town Hall in a concert of the Armenian National Chorus under the direction of Mihran Toumajan. His compositions were presented along with the work of his idols Gomitas and Sayat Nova, as well as his contemporaries Alan Hovhaness and Toumajan himself.

Portrait of Kurken Alemshah promoting a concert at New York City Town Hall, published in the September 25, 1947 edition of the Hairenik Weekly (Image source: National Library of Armenia)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

Zaruhi Elmassian & Setrag Vartian: On Stage & Screen

Setrag Vartian and Zaruhi Elmassian amazed and impressed audiences from stage to screen. Before meeting, they had each gained national recognition: Zaruhi as a singer and Setrag as an entertainer. Eventually eloping to Las Vegas in 1942, the couple became invaluable to the Armenian community through continued commitment to Armenian art and culture.

Written by Harout Arakelian

Zaruhi Elmassian

Born: Oct. 12, 1906, Lynn, MA

Death: Feb. 6, 1990, Los Angeles, CA

Active years recording: 1940s - 1950s

Label Association: MGM Records, Zar-Vart Records

Setrag Thomas Vartian

Born: Nov. 5, 1899, Dikranagert

Death: Apr. 23, 1986, Los Angeles, CA

Active years recording: 1925 - 1952

Label Association: Sohag Records, Zar-Vart Records

Setrag Vartian and Zaruhi Elmassian amazed and impressed audiences from stage to screen. Before meeting, they had each gained national recognition: Zaruhi as a singer and Setrag as an entertainer. Eventually eloping to Las Vegas in 1942, the couple became invaluable to the Armenian community through continued commitment to Armenian art and culture.

Setrag was born in Dikranagert, in 1899 and arrived in the United States in 1909 with his mother Mariam Vartian. They settled in Newark, NJ, just a short drive from Fort Lee, which by 1910 was America’s movie capital. There, Setrag grew up alongside the film industry. Zaruhi was born in Lynn, MA, in 1906; both of her parents were born in Kharpert.

Setrag married his first wife, Ankin, in 1921. Around that time the couple joined the Armenian Dramatic Society, led by Setrak and Masha Sourabian. In 1925, Setrag made his debut recording on the Sohag record label, with a song titled Jahel Em Gnig Chunim (I’m young and without a wife). By the end of the decade, the movie industry was shifting into a new phase with the “Talkies” (the addition of sound to motion pictures). In 1929, Setrag was signed with Fox Studios as a member of the permanent chorus.1 His lone credit is as a member of the chorus in the 1929 movie, Happy Days, appearing under the name Thomas Vartian.

In 1936, Setrag turned his attention to producing Armenian language films Establishing the Marana Films in NYC, Vartian would produce, direct, and star in the first Armenian language film made in America, a musical film adaptation of the popular operetta Arshin Mal Alan. The cast was primarily from the Sourabian’s acting troupe, with Setrag Vartian in the lead role. The film was screened in New York and nearly every Armenian community in America. Vartian, along with the Sourabians, moved to Los Angeles in the late 1930s to pursue opportunities in Hollywood and continue their advocacy for Armenian theater. Setrag Vartian would meet Zaruhi Elmassian in Hollywood.

Zaruhi Elmassian spent her childhood in Lynn, MA, but by high school the family relocated to Fresno. She began to gain local recognition for her soprano voice: her public debut was in 1927, at a concert held at Fresno State College. While attending the University of Southern California, she began appearing as a soloist for both Los Angeles and San Francisco Opera Companies. Zaruhi made numerous appearances on the radio in Southern California. In 1933, she appeared as the lead in a romantic opera titled The Master Thief, at the Pasadena Playhouse. In that same year she joined the Los Angeles Philharmonic, working alongside conductor Otto Klemperer.

Along with a handful of like-minded individuals, Zaruhi was integral in the establishment of the Armenian Allied Arts Association, a non-profit aimed at helping Armenian artists. Her magnificent voice and stage experience led her to Hollywood, where from 1933-1939, she lent her voice to ten major motion pictures. While some of the films leave her as uncredited, her highlights would be Naughty Murrieta (1935, which featured Armenian actor Akim Tamiroff), The Great Ziegfeld (1936, as a soloist). She’s credited as a vocal stand-in for Jeanette MacDonald, in three films, The Girl of the Golden West (1938), Sweethearts (1938), and Broadway Serenade (1939). In 1939, Zaruhi voiced one of the Munchkin’s in the movie the Wizard of Oz.

“The singer (Zaruhi) is endowed with a beautiful sweet voice which she commands and uses with ease. Listening to her, one cannot help but feel that her vocal resources are aided by unusual musicianship, adroit phrasing, and sense of style, which is so unusual among the singers of today.”

- Marguerite Babaian - Paris

After Setrag’s separation from his first wife, he and Zaruhi married in 1942. Setrag continued working in the post-production department for major film companies, such as RKO, Fox, First National, MGM and Warner Brothers. He also continued to produce and direct Armenian language films. In 1944, a film adaptation of Hovhaness Toumanian’s Anoush opera with music set by Armen Dikranian, was produced by Vartian, who called it the “first Armenian language film produced in Hollywood.” Setrag and Zaruhi would take the lead roles of Saro and Anoush. On October 29, 1944, the movie’s premiere screening was held at the Fresno High School auditorium and was attended by over 1,800 Fresno Armenians and other music lovers.3 Vartian’s last movie was a musical documentary, Songs of Gomidas Vartabed, in 1946.

The duo produced an album on their self-titled label Zar-Vart Records: Ooreni by Melikian, Hoy Nar by Sarkisian, Keler, Tzoler and Asoom en Oorin by Komitas Vartabed, Partzer Sarer by Tigranian, Astgher Anoush by Stepanian, and two duets, Arshin Mal Alan by Begoff and Siretzi-And-Haberban. The recordings shared here are from that album (with the exception of Strag’s 1925 recording of Jahel Em Gnig Chunim).