Karnig Kuludjian: Where are you going in this snowstorm?

Written by Jesse Kenas Collins and Harry Kezelian

The recording we focus on here is a simple and beautiful slice of life, put down on record 81 years ago to the month by Genocide survivor and Chicago resident Karnig Kuludjian. Unlike many of our other posts, what is remarkable about Karnig is not his impact on recorded history or the development of Armenian music; rather, it is the profound yet modest and intimate sense of purpose expressed in his gesture of marking on a home record the event of American troops returning home from Europe at the end of the war.

Home recordings have been a subtopic of the Sound Archive series: we have covered some aspects of the technology and its impacts in other posts, as well as showing their purpose of straddling commercial endeavors and documentation of important gatherings. In an age when most people have immediate access to recording technology, the sense of importance placed on the choice to record one’s voice at home in 1945 — when the technology was more difficult to operate and the medium to record on was expensive — can be hard to remember. It’s with that sense of importance that Karnig started up his record lathe one evening and expressed the following:

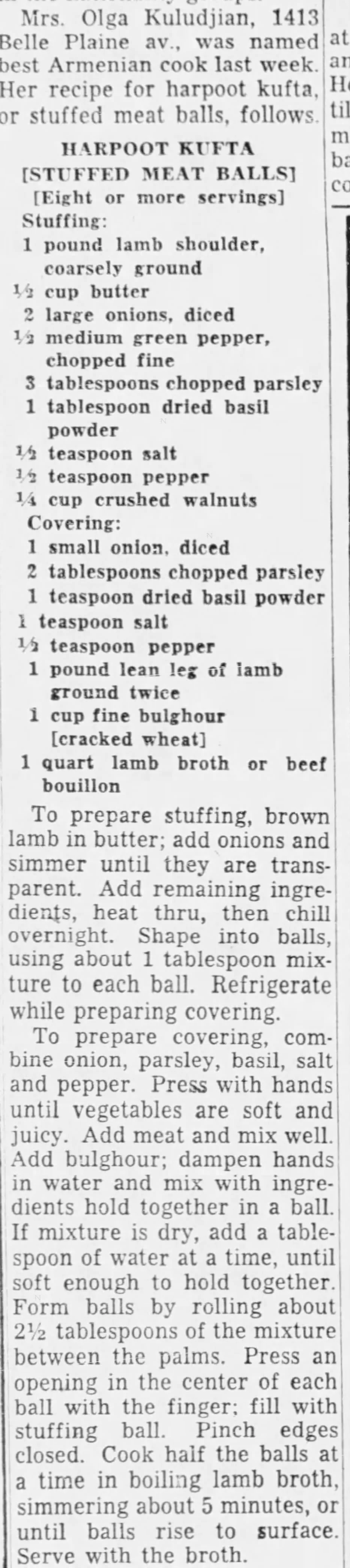

"This is February 3, 1945, soon the war in Europe will be over and all the Armenian boys are going to come back to America safe and sound. This is Karnig Kulujian. I am making this record in the home of my best friend, Ardashes Balabanian and we are going to sit here until everyone comes home, whether they throw us out or not, we are going to stay, and eat kufte and ghiyma until we burst.”1

Then he repeats the day and year and says that he is going to sing in memory of the Armenian boys far from home. What follows is a beautiful rendition of the song Gharib Aghper, which means something like "Exile Brother" or "Wandering Brother," and is about the wandering brother coming home. Though there is little documentation on the song, it appears the lyrics originated as a poem entitled "Gharib Mshetsin" by Shushanik Kurghinyan.

Gharib is an Arabic word meaning stranger, wanderer, foreigner, or exile. The concept of "Gharib" as a wanderer or emigrant who is far from home has deep roots in Armenian culture, going back at least to the 15th century poet Mgrdich Naghash, whose poems have been turned into songs by contemporary composer John Hodian with his "Naghash Ensemble." The poem "Gharib Mshetsin," meaning "Emigrant from Moush," was written by Eastern Armenian poetess Shushanik Kurghinyan. The words "Gharib Aghper," meaning emigrant brother, are the refrain of this song as the singer encourages the emigrant to come home with them, saying "where are you going in this snowstorm?" The singer encourages them to stay as "this is an Armenian hearth." The song finishes with encouraging the emigrant to share his woes and cry with the singer, as the singer says "my heart is in need of crying." The song was popular among political activist circles of the Diaspora as shown by its being performed by noted "revolutionary singer" George Tutunjian, affiliated with the ARF (of which Karnig was a member himself).

At the time of this recording Karnig was living in Chicago, IL, with his wife Olga and three daughters. He would later relocate to Lexington, MA, which in part explains this recording's path to the Museum’s collection. The emotional impact of Karnig’s singing and choice of song is deeply rooted in the severity of his experiences during the period of the Armenian Genocide. Born May 10th, 1900 in Divrigi in the region of Sepastia, Karnig, having already lost both his mother and father, was 14 when the Turkish military began the military conscription and later deportation of Armenians throughout the villages. Over the course of the next six years, Karnig witnessed and survived numerous atrocities until finding passage to the United States via Greece, thanks to the sponsorship of an uncle who had heard of Karnig’s survival in an Armenian paper in America. On Christmas Day 1920, he entered the US through Ellis Island and made his way to Chicago, where he was reunited with his uncle. He began working first in the cafeteria of the Armenian-run boarding house, and attended night school. Karnig then began a series of successful businesses, first as a cobbler and later starting a rug restoration and cleaning service. It was in Chicago that he met and married his wife Olga in 1925. Olga, though born in Chicago, had also survived the Genocide when her family returned to visit her grandparents in 1914. Both Karnig and Olga gave extensive testimony of their stories on December 5th, 1993; their full video testimonial is available through the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection. In researching this piece we came across a recipe for Olga’s kufte which Karnig mentioned they are eating on the night of the recording. The recipe was published in the Chicago Tribune on August 16 1956, we’ve included that clipping here in the spirit of their celebration.

Though what appears at first glance to be just a home recording of one song, this recording shares a dense story: it shows the grief and relief embedded in this historical moment as WWII ended, as documented by an Armenian man living in America who carried with him the knowledge of violence and atrocity that man is capable of, while also having arrived against all odds in a position of safety and opportunity in the United States through the support of others. It is this combination that makes this seemingly simple recording speak volumes.

1 This is a rough translation by Harry Kezelian. Due to the recording quality and Karnig’s dialectic accent, it does not represent an exact translation.

Still of Karnig Kuludjian from video testimonial given December 5, 1981 (Image source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of the Center for Holocaust Studies, Documentation, and Research)

Newspaper clipping of Olga Kuludjian’s kufte recipe featured in the August 16, 1956 issue of the Chicago Tribune (Image source: Newspapers.com)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.