O Swallow, Karekin Proodian and the Folk Interpretation of Armenian Patriotic Songs

This month’s music presentation features the intersection of so many aspects of the Armenian experience that it lends itself to the question, what makes a piece of music Armenian?

Many are familiar with the debates surrounding the influence of nearby Middle Eastern musical cultures on that of the Armenians, even including the translation of songs from other languages into Armenian. But oftentimes Armenian music held up as “classic” has also been translated from Western European languages, a perhaps lesser known phenomenon.

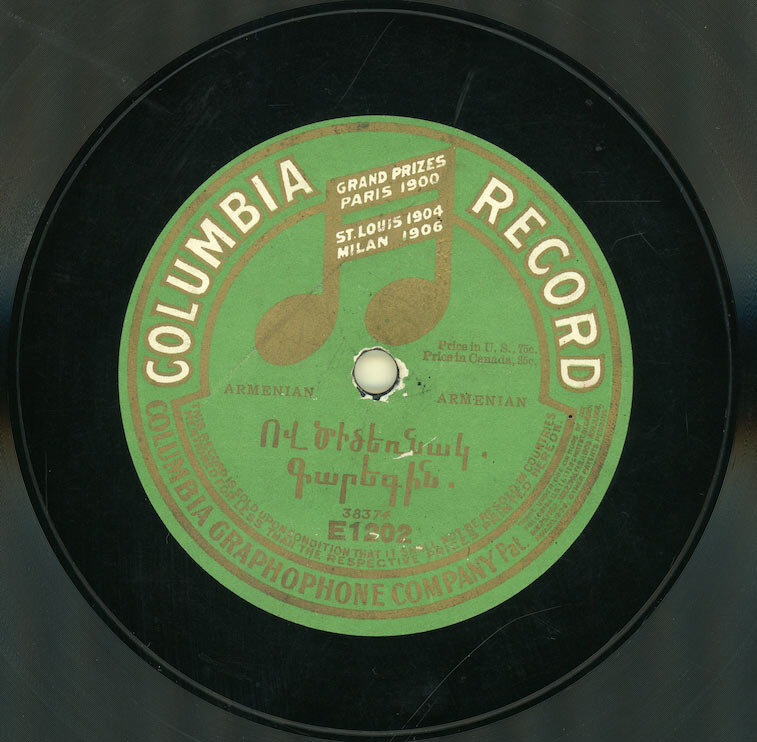

The artifact at hand is one disc recorded around late October of 1912 at the New York City studios of Columbia Records, of two Armenian songs by a singer whose name is listed only as “Karekin.” Based on the name, the recordings that took place at the same time and were listed before this one in the catalogs, and the vocalist’s voice, we presume that the artist is none other than Karekin Proodian (1884-1977) of northern New Jersey.

Proodian was a popular vocalist who made dozens of recordings in Middle Eastern languages in the 1910s and in Armenian in the 1920s. He had arrived in the United States on May 16, 1903, at the age of 18; around 1908 he returned to his native Dikranagerd (Diyarbakir) where he married his wife Haiganoush and had his first child. On June 5, 1912, the family returned to New Jersey and settled in the Dikranagerdtsi enclave of West Hoboken (later part of Union City, NJ).

Armenians in Dikranagert, circa 1912 ready for merriment with a kanoun, a violin, a waterpipe and a bottle of arak. Seated at far right is Karekin Proodian. (Image: Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives, Courtesy of Antranig Tarzian)

Proodian made his living in the lucrative photoengraving industry. His greatest musical success was perhaps as the interpreter of Anatolian style songs written in Western Armenian by the immigrant songwriter Hovsep Shamlian, also a Dikranagerd native. However, prior to his collaboration with Shamlian, Proodian had also recorded three other Armenian songs. One of them was Ashugh Sheram’s “Iprev Ardziv” (Like an Eagle), an ode to the heroism of General Antranig Ozanian. The other two were the songs presented today. In a sense, these are the first Armenian-language recordings in folk style produced in the United States, and some of the earliest in the world.

Though interpreted in a “folk” style, the two songs presented here are staples of the early “Armenian Classical” repertoire. Before the advent of the groundbreaking compositions and arrangements of Gomidas Vartabed, Armenians interested in performing a more Western style of music had, since the 1860s, developed a repertoire of mostly secular and patriotic tunes. One of the earliest such songs (which is still very popular today) was Dr. Nahabed Rousinian’s poem “Giligia,” set to music by Kapriel Yeranian around 1861, after Rousinian returned from a mission to Lebanon to help restore peace after the 1860 Mount Lebanon Civil War. Other early songs were inspired by the National Constitution of the Ottoman Armenians, promulgated in 1860 and ratified in 1863, which brought democratization and modernization to the Armenian community and in the drafting of which Rousinian, perhaps unsurprisingly, was a key figure.

In Constantinople, the operas of Dikran Tchouhadjian came next, along with a slew of patriotic songs (“Pamp-Vorodan,” “I Zen Hayer,” and so on). These works, as well as those by composers in Russian Armenia like Kristapor Kara-Murza and Armen Tigranian, paved the way for Gomidas Vartabed some 40 years later. Much of this early material was closely based on European, particularly French and Italian, models, and many of the lyrics were written by early Armenian nationalist poets from Russia like Kamar Katiba (Raphael Patkanian). American missionaries also translated English Protestant hymns into Western Armenian for their congregations; and the piano, organ, and violin began to be taught in Constantinople, Tiflis, and the provinces.

Larger and more Western-oriented Armenian schools even had string orchestras and marching bands. The work of Gomidas Vartabed brought a truer Armenian color to the already Westernized musical tastes of the Armenian upper class, in a Western format that they had grown accustomed to. However, since Karekin Proodian had a modal style of singing (likely learned as an acolyte or deacon in the Armenian Church in Dikranagerd), he interprets these two ostensibly “Western-style” popular patriotic songs in a more Eastern manner. And even though he is accompanied by a violin, a Western instrument, this is also performed in a modal, Eastern manner, most likely by Proodian’s brother-in-law, Hovhannes Malool, a native of Dikranagerd who was half-Armenian and half-Assyrian.

The two songs here are “Ov Dzidzernag” (O Swallow) and “Im Hayrenik” (My Homeland). The first, often titled as “Pandargyaln Ar Dzidzernag” (The Prisoner to The Swallow) is in a long tradition of Armenian folk songs addressed by a sad narrator to a passing bird, like the ever popular “Groong” (Crane). But this song wasn’t really written by an Armenian at all. Although an Armenian obviously composed/translated the Armenian version of the lyrics, the old songbooks always attribute the song to “Գրոսսի” (Krossi). This is identified as the little-known 19th century French composer Alexandre Croisez (1814-1886), who composed the original melody and published it in 1852 as “L’hirondelle et le prisonnier (Op.58).” The title translates as “The swallow and the prisoner,” and parts of the melody are even labelled “the swallow” and “song of the prisoner.” However, even though the prisoner is represented singing to the bird, there are no lyrics. Those apparently weren’t written until 1857, when John H. Hewitt, an American songwriter, got his hands on the song and added his own words. It appears that those words, loosely translated, are the origin of the Armenian lyrics.

Armenian lyrics to Ov Dzidzernag as printed in the Armenian-American New National Songbook, Volume 1 (Bedros Torosian, Hoboken 1917)

The sorrowful reflections of the inmate singing to the swallow who flies freely outside the walls of his cell were heartily adopted by Armenians, who must have likened the prisoner’s state to their own oppressed situation in “the hell called Turkey,” as many referred to it. “Ov Dzidzernag” became one of many popular Armenian political anthems of the late 19th and early 20th century, and it was practically the first song to be recorded in Armenian in the US, when it was sung by Mardiros Tashjian in 1909. What irony then, to learn that the original lyricist, John H. Hewitt, had gained most of his fame by writing songs in support of the Confederacy and even received the epithet “Bard of the Stars and Bars”!

THE PRISONER TO THE SWALLOW (only includes lyrics sung by Proodian)

O swallow, wavering little bird,

With what a sorrowful voice,

You make melody near my prison

Perhaps your sweet mate

Has left you all alone here?

And you sob inconsolably

Oh, then weep you like me!

The second song, “Im Hayrenik” (My Homeland) is also interpreted by singer and violinist in an Armenian modal manner. The song lyrics are attributed to one H. Haigouni, which is possibly a pseudonym used around 1910 by a political activist of the Ramgavar Party originally from Aintab. The composer is unknown to us thus far. The same commentary which applied to the former song is also applicable here.

IM HAYRENIK (My Homeland)

My homeland calls to me

I am far from Armenia

Does it befit the son of an Armenian

To go away from Armenia?

Buried in deep sadness is

Queen Armenia

She who laments for her sons,

Pitiable Armenia

Proodian, who in addition to his singing played the dumbeg and kanoun, had a long career ahead of him, which is outside the scope of this article. Proodian’s son Set also became active in Armenian music as a saxophonist and clarinetist.

Portrait of Karekin Proodian in a song book published by the Sohag record label in the early 1920s (Scan from The Mesrob G. Boyajian Library at the Armenian Museum of America)

A special thanks to the SJS Charitable Trust for their generous support of our work to digitize and share our collection of 78 rpm records.

A special thanks to Jesse Kenas Collins, Harry Kezelian, and Harout Arakelian whose ongoing contributions of research and consultation have been critical to assembling the writings presented here.