The tar and the work of Haig Ohanian and George Shah-Baronian

The tar, a long-neck lute, has been a central instrument of Armenian folk music for centuries. The instrument has an hourglass-shaped body carved out of mulberry and covered with a vellum made of cow heart. It usually has between six and eleven strings, and twenty-five to twenty-eight adjustable frets (which determine the notes and scales playable on the instrument). (Continue reading below.)

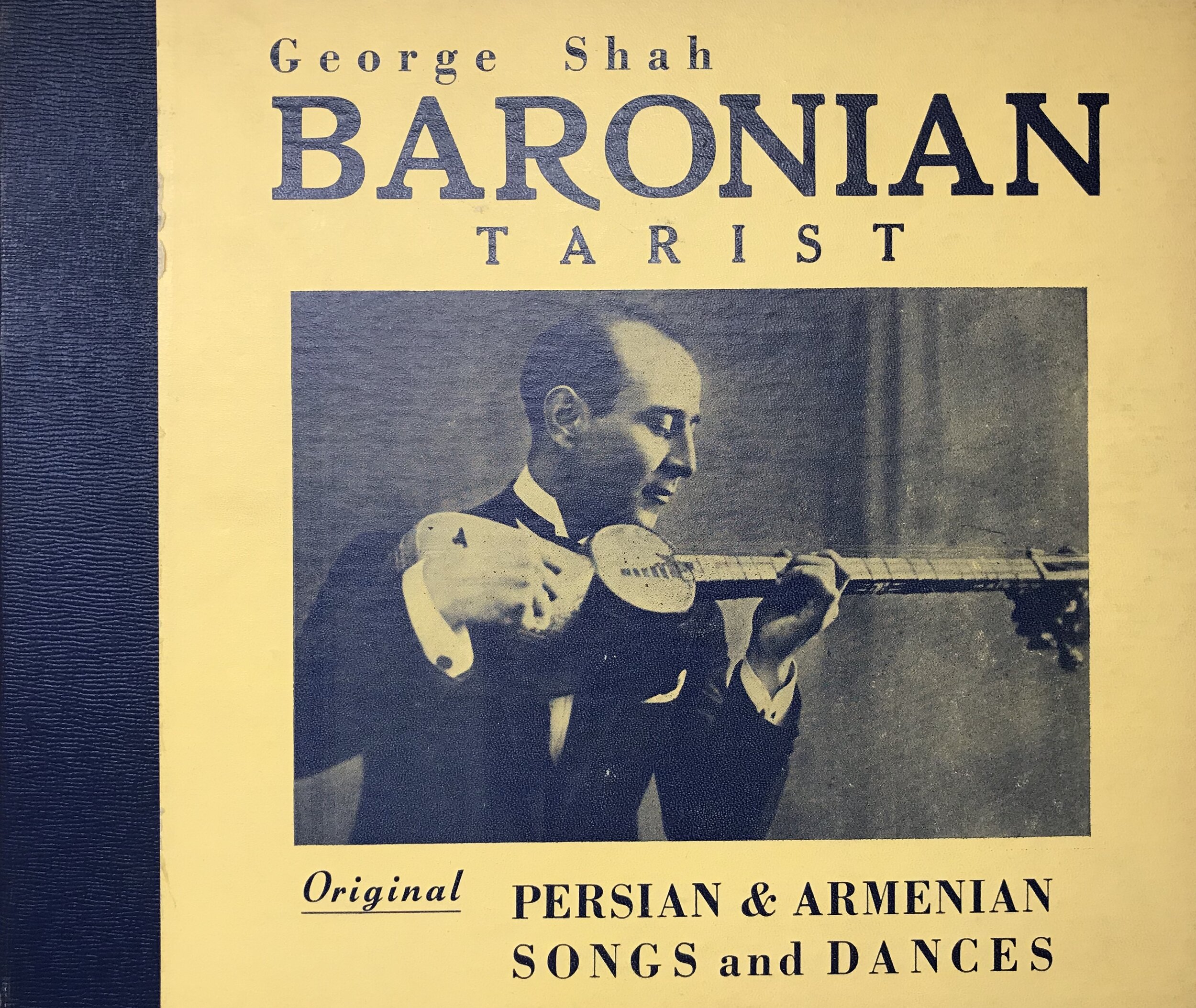

In the Sound Archive of the Museum are several recordings by two Armenian tar players and entrepreneurs, who recorded and performed extensively on this instrument in the United States. They are George Shah-Baronian and Haig Ohanian. Both operated their own private record labels to publish their works, and both presented the traditional and historical repertoire of the instrument while also modernizing its use in the context of American popular music.

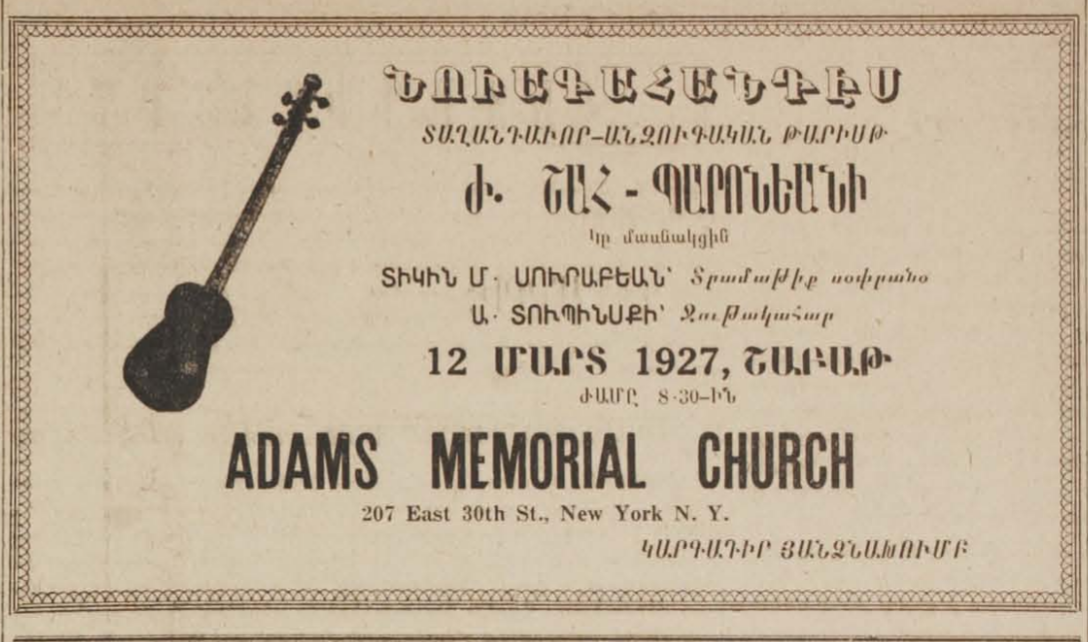

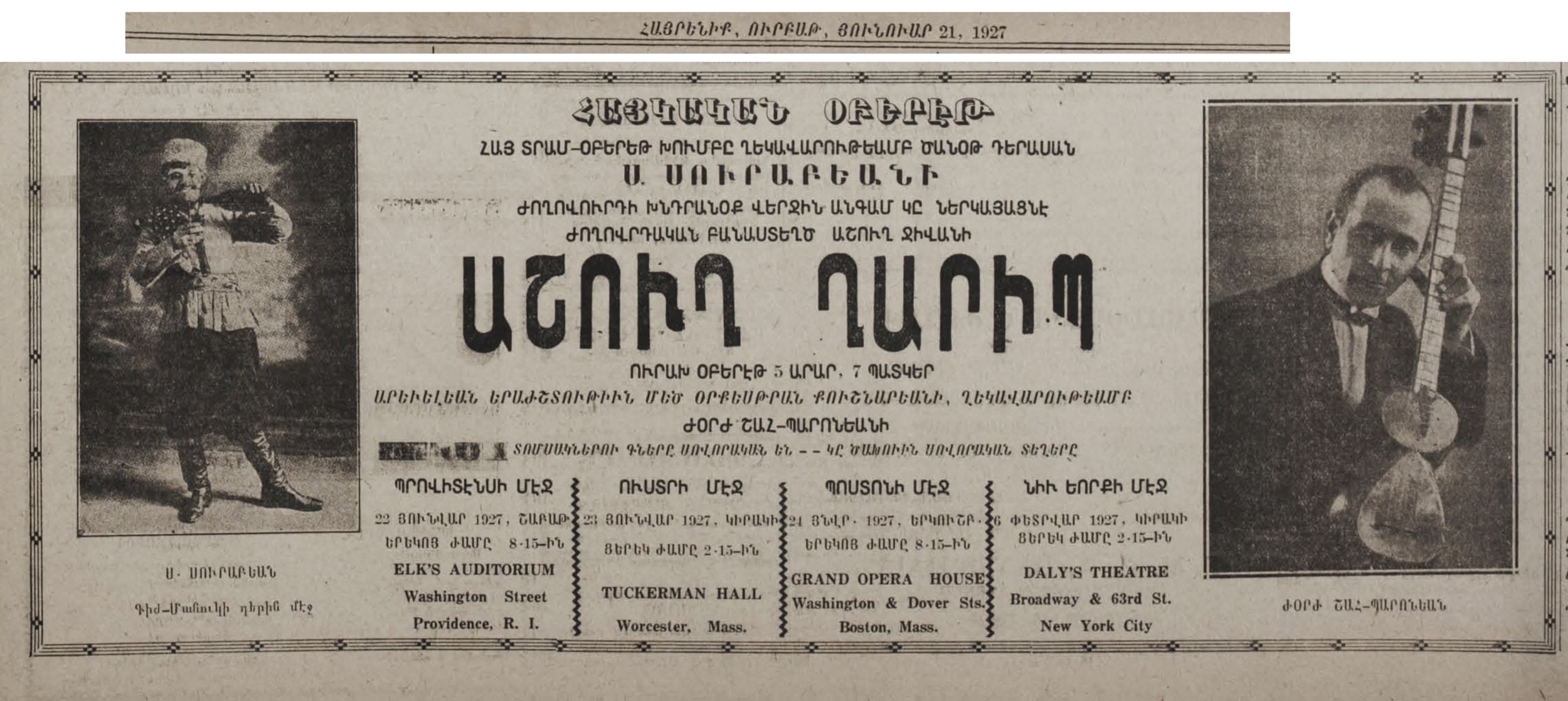

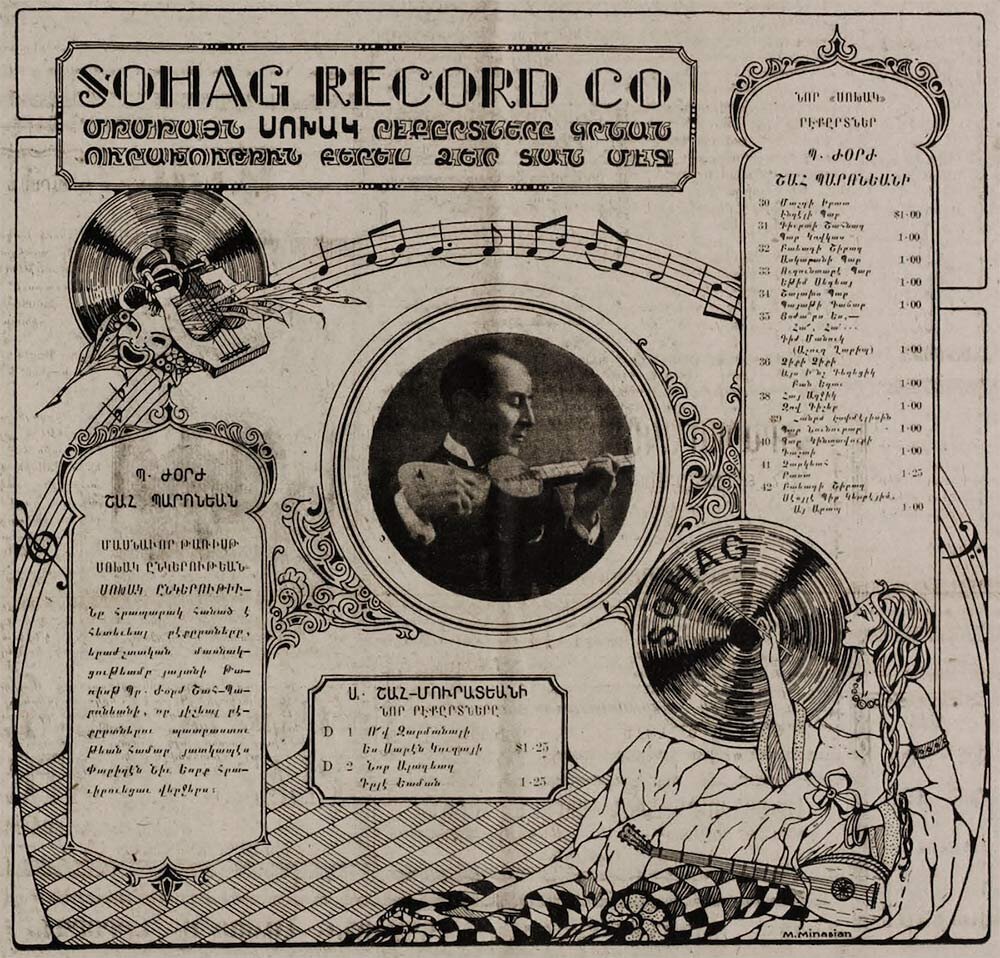

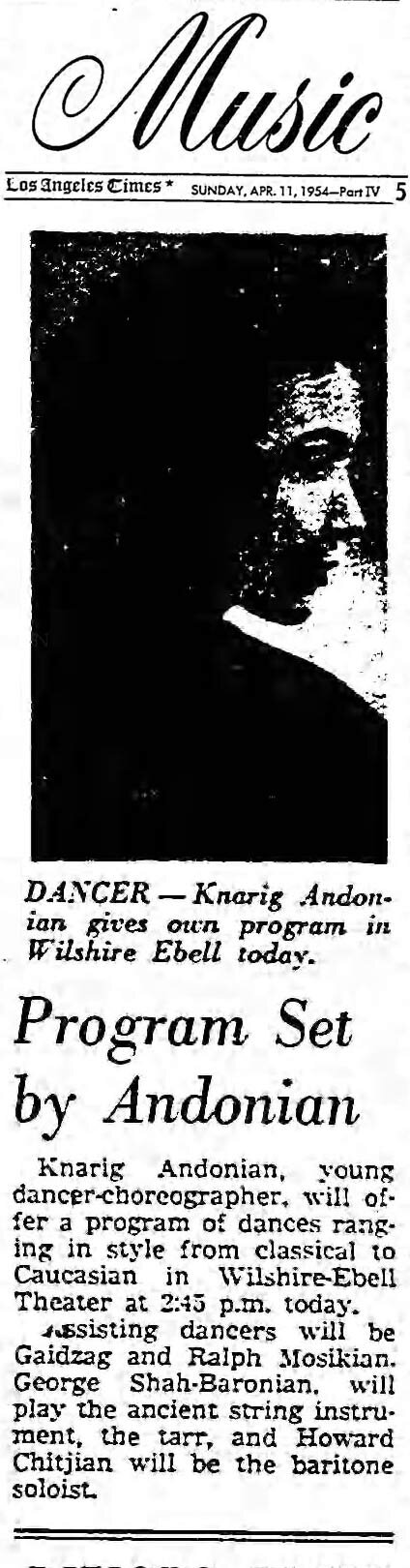

George Shah-Baronian was a highly accomplished Armenian tarist and composer born in Tabriz, Iran in 1897. After having spent his youth in Tiflis, where he would also receive his music education, he came to the US with his wife Genia in 1926; by 1927 he was appearing on records for the independent Armenian labels Sohag and Pharos in New York City. The couple left the states for Paris, where by 1929 Shah-Baronian would perform on stage and on the radio. It is assumed that during this time George took up his study at the Paris Conservatory. By 1937 they returned to the US, living and performing in New York City and Chicago; the couple would later settle in Los Angeles, California. During this period George began work writing compositions for film, including contributions to two films from 1951, Sirocco starring Humphrey Bogart and Magic Carpet starring Lucille Ball. In the early 1950s he published a set of recordings featuring himself on tar along with Genia on the piano. The tar solo recordings on these discs display George's command of traditional forms, including a wonderful rendition of the song “Grung'' heard here. Genia’s approach to the piano, as heard on their rendition of the dance song “Naz-bar,” begins to merge the distinct and ancient timbre of the tar with a kind of popular American style. This merging of the traditional and the modernist likely grew out of George’s practice in film composition, and a life lived around Hollywood during its golden age. He was also an important musician for the Los Angeles Armenian community. George and Genia would perform at many benefit concerts, especially during the community efforts to help the Displaced Armenians in Post-War Europe.

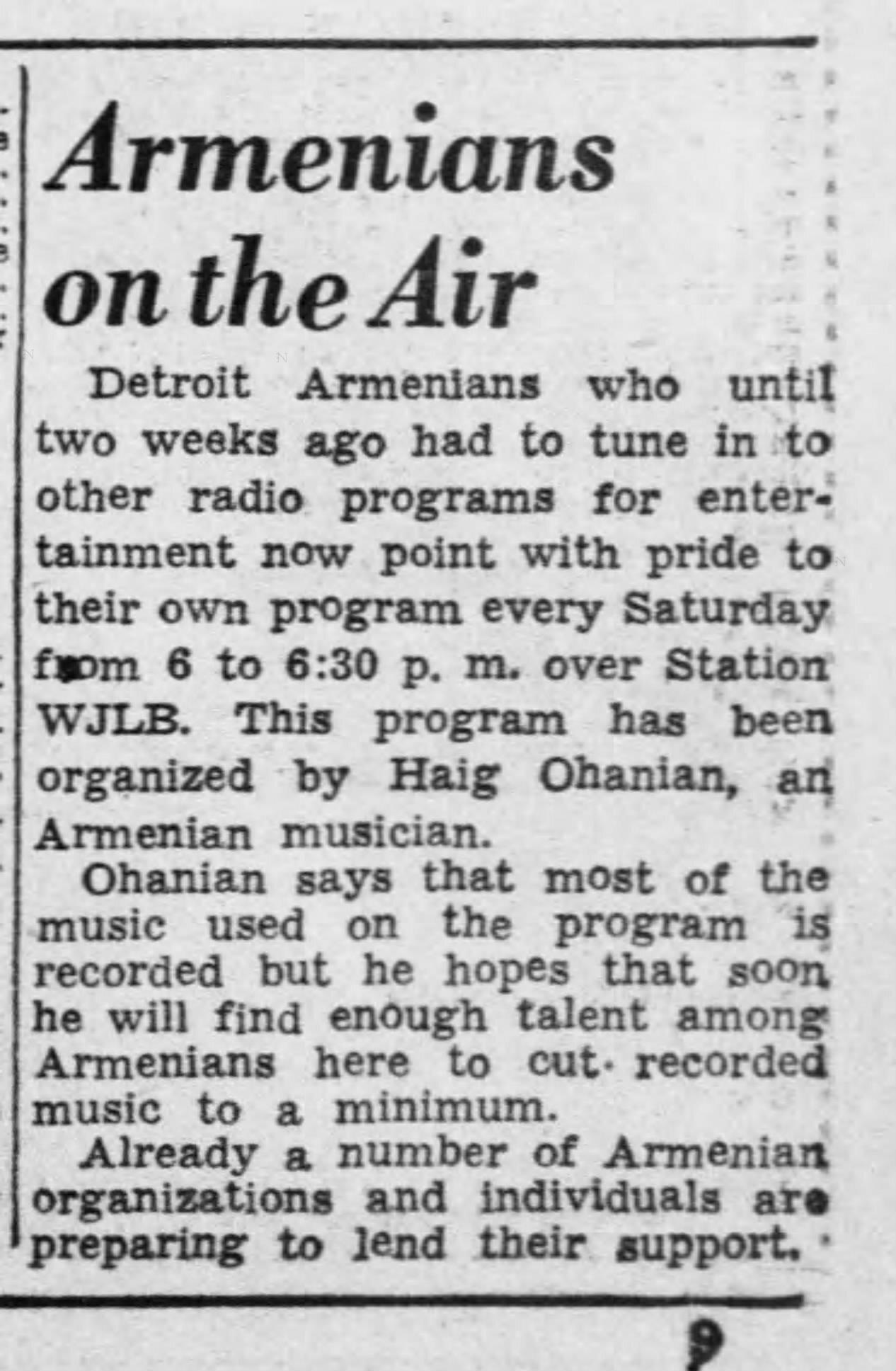

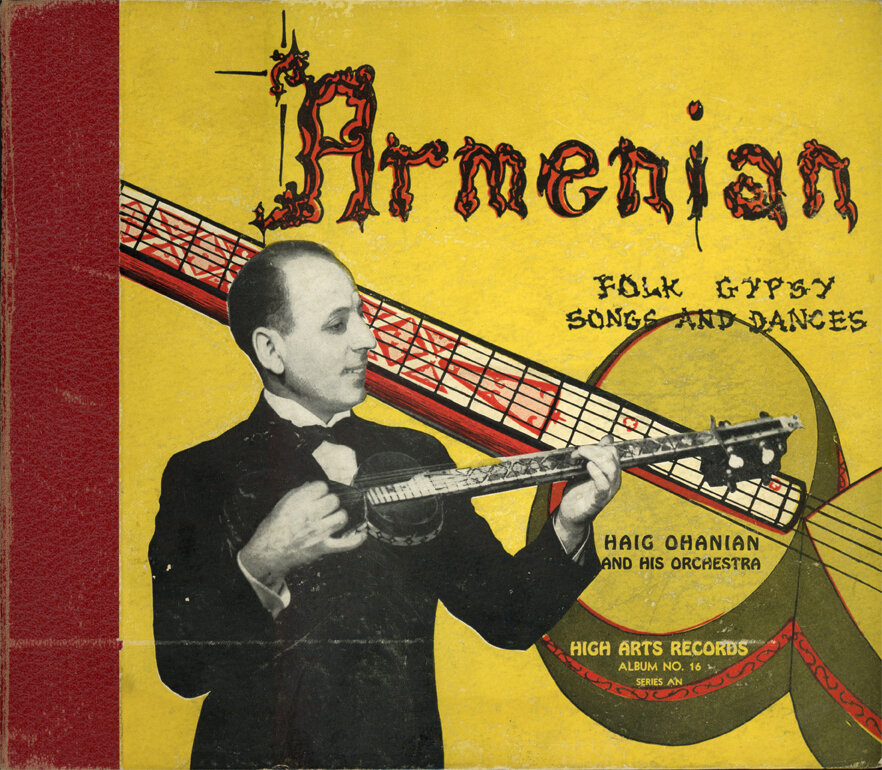

Parallel in many ways is the work of tarist Haig Ohanian, born in 1904 in Tiflis. He performed and recorded actively in the Detroit area throughout the 1940s. During that time he ran his own label, High Art. The records on this label were issued in album sets of 4 discs, most of which featured a tar performance by Ohanian with a small ensemble on one side, while the other side featured female vocalists performing Armenian classical and operatic songs. Presented here is a disc produced by Haig with the singer Maria Arakian, which actually appears to predate his High Art label. In addition to his recordings and performances, Haig was also active in radio and hosted an Armenian Radio Hour in Detroit throughout the 1950s. While his activity and whereabouts later in life are unclear, he appears to have relocated to the New York area by the 1960s, where he continued to operate his Armenian Radio Hour, and he is documented to have been performing in New Jersey as late as 1982. Haig, like George Shah-Baronian, was deeply involved in the history of his instrument and in newspaper features made claims of his own instrument being over 300 years old. While we have no way of verifying that claim, at the very least it attests to Haig’s sense of the instrument as a link between himself and the history of his music and culture. But as with George Shah-Baronian, Haig was a distinctly modern man and entrepreneur who fully incorporated the new American context in which he worked. To this end, he performed his arrangements with a group of non-Armenian musicians, an approach that merged his unique and traditional instrument and songs with distinctly American characteristics.

This narrative is not entirely unique within Armenian-American performers of the time. Throughout the 1940s and 50s, many Armenian dance bands emerged that paired ouds with clarinets and saxophones. But while these instruments melded more seamlessly with the instrumentation of jazz and popular American music, the tar stands out in this context, declaring through its bright timbre its link to a rich musical past.